Azrieli Best Book in Israel Studies Review (2024)

By Randy Pinsky

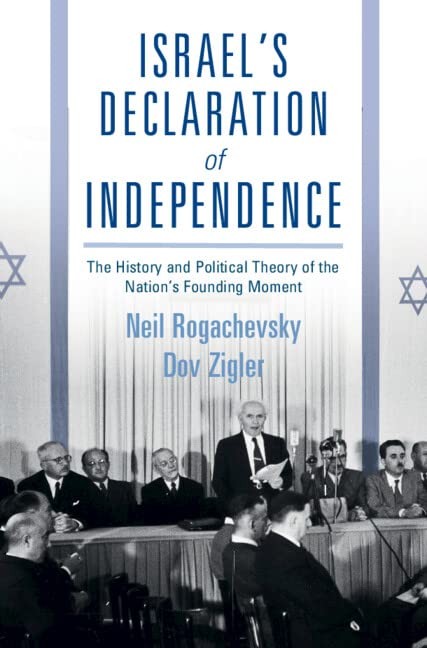

Israel’s Declaration of Independence: The History and Political Theory of the Nation’s Founding Moment

by Neil Rogachevsky and Dov Zigler

It is fitting that the 2024 Azrieli Best Book Award goes to the first comprehensive English analysis of Israel’s Declaration of Independence, just in time for Yom Ha’atzmaut and Israel’s 76th anniversary. In Israel’s Declaration of Independence: The History and Political Theory of the Nations Founding Moment, Neil Rogachevsky and Dov Zigler engage in a comprehensive analysis of the “intellectual journey” of this key document. Through delving into recently released meeting minutes and the endless debates in its drafting, they examine both the nuances of the historical process, as well as the declaration’s implications for Israel’s contemporary political landscape.

What was the process of “turn[ing] the Jewish people’s national hope into a state”?[1] Who decided what to include and, alternatively, what to omit in the final document? The Declaration’s central symbolic role as a unifying force across time, its nuances and implications, demonstrate its perpetual relevance to Israel and its people.

Setting the Stage

The time: May 1948. The context: planned British withdrawal from the region after controlling it since 1918. The situation: The need for a sovereign state of Israel.

With the planned British evacuation and rumblings of an imminent attack by Arab neighbors, members of the Yishuv (pre-Israel community) ascertained the immediate need to formally establish a modern Jewish state. It would take exceptional diplomatic efforts, but the United Nations would ultimately approve Resolution 181; a Partition Plan which would create one Jewish and one Arab state.

It was critical that a formal Declaration of Independence be released in order to rapidly and strategically organize the burgeoning country’s government and military capabilities.

A State Within Reach

Following the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the British ruled pre-state Israel for decades, wooing the Arab oil barons and giving them favorable treatment in the region. In recognizing the bias against them, a scrappy and chutzpadik group of Jewish pioneers defied orders to have unofficial self-rule and self-defense in their historic homeland. Although with the passing of Resolution 181, a state of their own was finally within reach, it would not be without first going through the inevitable ‘tovo bohu’ or “formlessness and chaos” of a power transfer.

There was thus a critical need to draft - and quickly - a declaration of independence prior to the British withdrawal (first Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion would read the document a mere eight hours prior to the “expiry of the British mandate”).

The declaration would need to evoke the sentiment and goals of the new state, present its priorities and values, and serve as a guiding document. It would take five versions and endless debates, elucidating the priorities and needs of the time.

The Drafting Begins

What to include and what not to? This was a daunting challenge for even the most accomplished wordsmith. Through analyzing the various drafts, authors Rogachevsky and Zigler[2] explored how some emphasized religious references while others, the ethos of Labor Zionism, yet all were united in the need for a sovereign Jewish state.

They powerfully encapsulated the emotional moment: “the act of a declaration of political independence represented a shift from stateless to a state…from being ruled to ruling...opening…a new volume in Jewish history”[3]. The document not only asserted Israel's independence but also the need for a state “by virtue of our natural and historic right”.[4]

Indeed, Israel’s future foreign minister Moshe Sharett, a critical player in the Partition Plan, would write in his version of the declaration, “whereas the persecution that has been visited from time immemorial upon the masses of Israel in different lands…has proven anew the urgent necessity of a solution…through a renewal of national independence in their land, so that its gates will be permanently open to all Jews seeking a home.”[5]

Much of his wording, or at least the impassioned appeals, would remain in the final version which would reinforce, “The Jewish state will be a state of the in-gathering of the exile for Jews, [one] of freedom, justice and peace.”[6]

Israel was ahead of its time in stipulating equality of rights and opportunities for all, regardless of gender, religion or minority status, hinting at a desired diverse population make-up. The authors of the Declaration drew extensive inspiration from the American Declaration of Independence, from the outset, expressing a stated commitment to “one law for all.”[7]

A Document Unlike Any Other

While the drafters could not have known it then, the declaration would bear timeless relevance, being “the only statement that address[ed] the foundational questions for equality, [social and political] rights and minorities in Israel.”

It set out a vision of the new country based on three factors: a strong independent and sovereign state; for it to be a Jewish state; and to be one with rights and equality for all- mutually reinforcing conditions for forthcoming laws and institutions.

The “Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel” - as it was officially known - would be read before a crowd on May 14, 1948; “the worst kept secret in Tel Aviv”.[8] The momentous event took place at the Tel Aviv Museum, chosen as it was “believed to be less susceptible to Egyptian aerial bombardment than the larger and better outfitted Habimah Theatre down the street”.[9]

Celebrations at its announcement were short however as the new state had to immediately start defending itself against hostile surrounding Arab nations. Defying all odds, Israel defeated its enemies, losing 1% of its tiny population in the process but making a name for itself in the region.

America: the Maker or Breaker

Upon working towards statehood, there was uncertainty about how it would be received by other countries. Pre-state Israel “faced a diplomatic test as the members of its council struggled to peer into the murk and fog of international politics to discern… the global reaction.”[10]

At the time, the United States was cautious in fully endorsing the young state. While President Harry Truman supported it, his Secretary of State George Marshall insisted on presenting counterarguments, questioning if it was in America’s best interest.

Already in the throes of Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union, the US feared endorsing Israel could result in the Arabs allying with it. Not only would this be concerning on a geopolitical scale, it would also have repercussions for oil-dependent America (which the Arab countries were well aware of).

Marshall voiced how an “American backing of a Jewish state seemed potentially costly, dangerously and needlessly antagonistic of important allies in the Middle East whose oil would power the hoped-for [alliance and] economic recovery [of Europe]”.[11]

Some Shady Business

In the effort to forestall American approval for statehood, Truman’s own office conspired to delay or confuse messages, such as remarking on meetings held by a “Mr Ben Gurion.”[12]

In the biography about her father, Truman’s daughter shared how he was “livid upon learning of the State Department's maneuver…[stating that it] ‘pulled the rug’ from under him”, in what his Administrative Assistant argued was an attempt to “deliberately ‘garble’” his instructions.[13]

Truman ordered a reversal of the position, but the damage had been done. The American Consul General in Jerusalem stated, “most feel [the] United States has betrayed Jewish interests [for] Middle Eastern oil and for fear [of] Russian designs.”[14]

Ah ah ah, Peace First

Another means for preventing Israel’s independence was seeking to reinforce the literal interpretation of Resolution 181, stipulating peace in the region as a precondition to partition.

Sharett condemned this attempt at state sabotage, claiming that pushing for this precondition “comes as a reward for the campaign of violence now being conducted against that Resolution and encourage[s] the forces of defiance to redouble their efforts.”[15] Even if reaching political reconciliation in the region had been possible, there was no confirmation that this would guarantee forthcoming American support.[16]

The government also attempted to prevent Americans from enlisting to fight for the Yishuv. “Had this ban been strictly enforced, it might have been crippling: of the 193 pilots who flew for Israel in the War of Independence, over half were Americans who chose to ignore the law.”[17]

When he found out, Truman condemned such acts. “I feel that Israel deserved to be recognized and didn’t give a damn whether the Arabs liked it or not.”[18] The US would officially recognize the new state at midnight on May 14, the first country to do so.[19]

Nuances and Ambiguities

As noted by Moshe Smoira, first president of Israel’s Supreme Court, the Declaration reveals “the nation’s vision and its basic credo”, and continues to do so to this day.[20]

While it is widely agreed as representing “‘the national consciousness’ of the people”,[21] it is too vague and ambiguous in its wording to be used as a constitution or legal document (though some have tried).[22]

In particular, the ambiguity on “how Judaism should inform the politics or the life of the Jewish state,” stated Rogachevsky and Zigler, is “[an] unresolved character… [which] is perhaps the central tension of modern Israel.”[23]

“The National Consciousness of the People”[24]

In a highly divided Israeli society, the Declaration is a unifying force, connecting the past with the present and future[25]. “This is the source of our nation’s values,” Rogachevsky stated in an event with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on May 7, “a necessary starting point.”

By gaining independence, Israelis “would be[come] masters of their own fate in their own sovereign state,” affirmed Ben-Gurion.[26] Timeless and unsurpassed in its ability to unite, “Its words capture the spirit not of a person or a party - but of a people.”

[1] Rogachevsky, Neil and Dov Zigler. 2022. Israel’s Declaration of Independence: The History and Political Theory of the Nations Founding Moment, Cambridge University Press: 1.

[2] Neil Rogachevsky is Clinical Assistant Professor and Associate Director at the Straus Center of Yeshiva University, and Dov Zigler is Chief International Economist at Element Capital in New York.

[3] Ibid: 3-4

[4] Determination to realize a historical wish recited every year at Passover (“Next year in Jerusalem”): 7

[5] Ibid: 144

[6] Ibid: 259

[7] Ibid: 83

[8] Ibid: 2

[9] Ibid: 1

[10] Ibid: 140-141

[11] Ibid: 152

[12] David Ben-Gurion was the first Prime Minister of Israel and final editor of the Declaration: 265.

[13] Ibid: 154

[14] Ibid: 152

[15] Ibid: 156

[16] Ibid: 157

[17] Ibid: 158-159

[18] Ibid: 162

[19] Ibid: 15

[20] Ibid: 8

[21] Ibid: 258

[22] Ibid: 259

[23] For instance, how does one balance ‘rights and equality for all’ with religious exemptions from military service? This historical tension has been of particular relevance in the Israel-Hamas conflict. In fact, the Declaration was invoked by the Supreme Court in Movement for Quality Government v.the Knesset (2006) regarding the legality of the Tal Laws which had formalized this military exemption: 249, 273.

[24] Ibid: 258

[25] Ibid: 262

[26] Ibid: 262