The COVID-19 pandemic brought the longstanding economic inequalities between women and men into sharp focus. From the onset of the pandemic, up until the summer of 2022, economic gender gaps continued to widen.

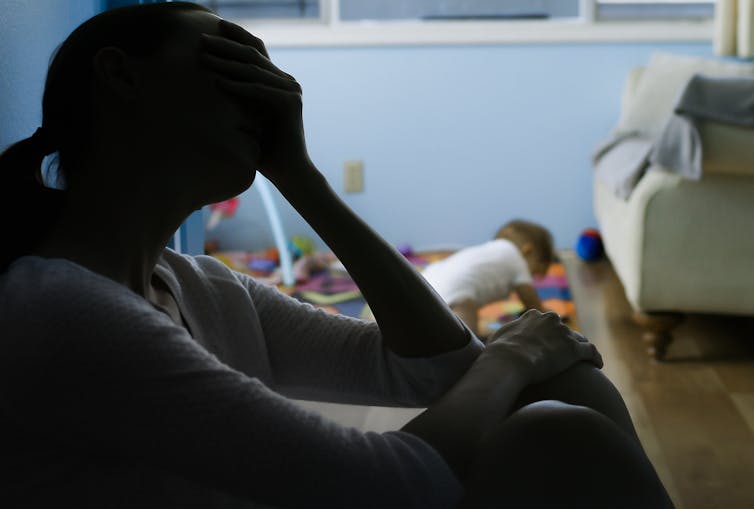

Lockdowns and economic uncertainties created a perfect storm, leading to job losses and reduced opportunities for women in the workforce. The increased burden of caregiving responsibilities placed an additional strain on women, often forcing them to make difficult choices between their careers and family obligations.

The situation peaked in 2020 when women’s workforce participation plummeted to levels not seen since the 1980s. This decline marked a concerning setback in the progress women had collectively made in the workplace over the past few decades.

Now, looking back at how these gender inequalities have evolved since 2022, the overall picture is a bit more complex. The most recent data from Statistics Canada shows that, while gender inequalities remain fairly large between women and men, there are also some exceptions.

Inequality in the labour force

Economists refer to people who look for paid work as being “in the labour force.” In terms of men and women who were looking for paid work in 2023, gender inequalities have not changed since the previous year.

Like in 2022, men are still more likely than women to be in the labour force in 2023. By November 2023, 71 per cent of men were looking for paid work, compared to only 61 per cent of women.

What accounts for this gender gap? Women’s absence in the labour force is often referred to as a personal choice for taking care of children. Many couples, faced with high childcare costs, decide that one parent should stay home. Given that men’s take-home pay exceeds women’s, this parent usually ends up being the mother in heterosexual relationships.

However, what is sidestepped in framing this as a choice are the broader societal conditions that contribute to this choice. Women’s absence from the labour force is often not a choice, but the result of factors outside their control.

A good example is the high cost of childcare, which the federal government is trying to address with its $10-a-day childcare plan. While some cities have seen childcare fees drop as a result, others are still falling short of the federal government’s target.

Another contributing factor is the undervaluation of professions that tend to consist primarily of women, like nursing and care work, even though they provide services crucial for society, as anyone who has been to the emergency department knows.

Gender and unemployment

When it comes to unemployment, the gender gap has dramatically changed: fewer women were unemployed in 2023 than men. In November 2023, five per cent of women in the labour force were unemployed, compared to six per cent of men.

This is a reversal from 2022, when more women were unemployed than men. While a gender gap in unemployment still exists, it now favours women slightly.

Shifting focus to employed individuals and the gender gaps in both part-time and full-time employment, the data shows that men in the labour force are more likely to have full-time jobs than women. In November 2023, 82 per cent of men in the labour force worked full time, compared to slightly less than 72 per cent of women.

Men, like women, worked less full-time in 2023 than in 2022; however, the decrease in full-time work has been most pronounced for men. In August 2022, 84 per cent of men in the labour force held full-time jobs, compared to slightly more than 72 per cent of women. The gender gap in full-time work continues to favour men, although it is narrowing.

The opposite is true for part-time work — women continue to work part-time more than men, with 23 per cent of women working part-time, compared to 13 per cent of men. This is an increase from 2022, when 21 per cent of women and 10 per cent of men worked part-time.

Overall, the gender gap in part-time work continues to favour women: women are still more likely to work part-time than men.

Burden of childcare

Statistics Canada’s data on why people work part-time sheds light on the gender gap in part-time work. In November 2023, slightly less than 27 per cent of women aged 25 to 54 worked part-time because they cared for children, compared to only 4.5 per cent of men.

This gender gap has widened since August 2022, when nearly seven per cent of men worked part-time because of caregiving, compared to a bit more than 27 per cent of women.

The slight drop in women working part-time due to caregiving could be explained by the Canada-wide Early Learning and Child Care Plan, which made childcare more affordable.

Traditionally, social norms hold women, not men, as the primary caregivers. These norms could explain why fathers, more than mothers, stop working part-time because of caregiving when affordable childcare becomes available. However, research is necessary to provide a definitive answer.

Policy interventions, workplace reforms and community support are pivotal in creating an environment that empowers women to participate in the workforce and men to participate in carework at home.

Initiatives that address the root causes of gender disparities, such as affordable childcare, can contribute to levelling the playing field. Moreover, workplaces can help level the playing field by enabling and encouraging fathers to take paternity leaves. By understanding the factors at play and actively working towards solutions, we can work towards addressing and rectifying gender inequalities.![]()

Claudine Mangen, RBC Professor in Responsible Organizations and Full Professor, Concordia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.