Breast stories: Life after cancer

The average woman probably doesn’t spend much time questioning her relationship with her breasts until she’s faced with losing one or both to cancer.

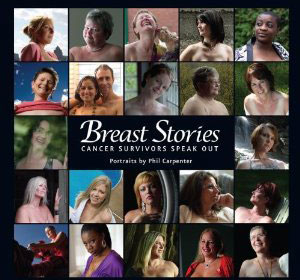

In Breast Stories (Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 109 pages), photojournalist and Department of Communication Studies alumnus Phil Carpenter documents the experiences of 53 Canadian women — from British Columbia to Newfoundland — who have undergone mastectomies.

Carpenter’s striking photo essay forces the uninitiated reader to face the disquieting reality of each woman’s scarred chest: reconstructed, lopsided or flat as a child’s.

“I want the book to get people talking about the issue, instead of hiding it away. If we get used to seeing images like this, hopefully it will be easier for at least some women who go through a mastectomy,” says Carpenter, a photo- and video-journalist at The Gazette and a part-time instructor in Concordia’s Department of Journalism.

In the unique portraits, some women bear their scars with expressions of pride or joy at being alive. In others, we see traces of sadness or hope. The reactions are as varied as the women themselves, aged 30 to 66, who range across the professional spectrum from scientist to nurse to aesthetician.

In the accompanying stories, each woman tells of her own changing relationship with her breasts through the mastectomy experience — how it affects her femininity, sexuality, sense of self, and how others look at her.

In the book, 47-year-old Julie Porter writes, “It took some time before I felt comfortable enough to undress in front of my husband.”

Thirty-four-year-old Bernadette Leno writes, two weeks after both her breasts were removed: “I’m just now beginning to venture out in public and I can’t help but try and gauge the reactions of the complete strangers I pass by on a daily basis.”

The idea of documenting the before-and-after of a mastectomy came in 2006 when Carpenter was approached by Deborah Parkes, his former colleague at The Gazette. She asked him to document her second mastectomy, taking before and after photos. “I didn’t know what to expect, but here she was trusting me to see her half naked,” says Carpenter.

“That experience got me thinking about doing a photo essay exploring how women and men look at femininity and the role of breasts in defining it,” Carpenter says.

Later that year, his first photographic profile of six Montreal women who had had mastectomies appeared in The Gazette and went on to win an award from the Society of News Design.

A couple of women he photographed pushed hard for Carpenter to expand the essay into a book. They felt it would be helpful for other women facing mastectomies, since the only pictures available online were clinical and, in their view, dehumanized women.

“I started the project wanting to show that breasts should not define women. I wanted to shoot only women who had not had reconstructive surgery. But in the process, I came to understand the issue is much more complicated and multi-layered than I had thought.

“Each person’s relationship with her breasts is different, even growing up, and the fact that someone has reconstruction doesn’t mean that she defines herself by her breasts. Alternatively if a woman does define herself that way, that doesn’t mean she should be excluded. It’s all part of the story. I learned that there is no right way to see it.”

Carpenter spent more than $12,000 of his own funds and much of his vacation time to produce the book.

“His photographs are beautiful portraits that enhance our understanding of the ravages of breast cancer and help to teach us about what happens after. His sensitivity and skill allows participants to share deeply profound, moving, unique and inspiring experiences that provide women with insights into coping and surviving,” says Rae Staseson, chair of Concordia’s Department of Communication Studies.

Looking back to his university days, Carpenter attributes his understanding of different forms of storytelling and what works best for a particular story to the Communication Studies program.

While a student at Concordia, Carpenter joined the Canadian Forces as a reservist with the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada. After his 1997 graduation, he began freelancing as a photojournalist, primarily for The Gazette, where he was hired as a staff photo- and video-journalist in 2005. He has covered the earthquake in Haiti, the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide and Canadian peacekeeping operations in Bosnia.

Related links:

• Breast Stories

• Concordia Department of Communication Studies

• Concordia Department of Journalism

• The Gazette