'Joyceans are the Star Trek fans of the book world'

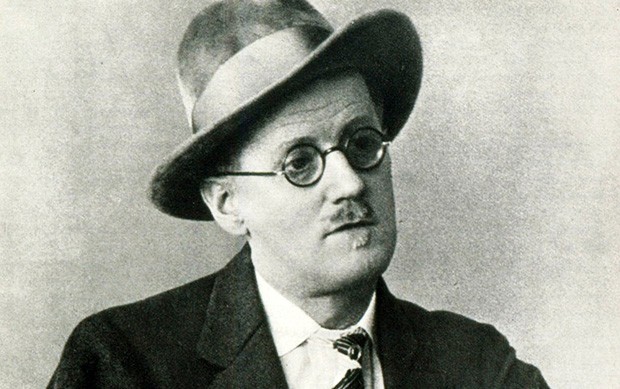

James Joyce set Ulysses on June 16, 1904 – the date of his first rendezvous with his wife-to-be Nora Barnacle.

James Joyce set Ulysses on June 16, 1904 – the date of his first rendezvous with his wife-to-be Nora Barnacle.

"With Bloomsday now being celebrated in at least 60 cities in more than a dozen languages, it seems there is no escaping a Joycean mid-June," writes Emer O'Toole, assistant professor at Concordia's School of Canadian Irish Studies. "Why? How has this occasion become so large in scale?"

The following is excerpted from O'Toole's "What is culture for? Thoughts on Bloomsday, Ireland and the diaspora," a 2014 address for Montreal's June 12-16 Bloomsday Festival.

Bloomsday, as we all know, is June 16th, and is celebrated to commemorate the fictional date in 1904 that Joyce paints with such flair in Ulysses — seen by most as the foundational text of modern Irish literature and many as the greatest text of the modernist movement. This week, like thousands of other people around the globe, we are gearing up to celebrate the 111th anniversary of Leopold Bloom’s peripatetic day in Edwardian Dublin.

Joyceans are the Star Trek fans of the book world: they dress up, they re-enact things, they impress each other with fan paraphernalia and trivia. In this regard, Bloomsday really is quite an unusual thing.

As Isaiah Sheffer (a great proponent of Joyce, who sadly died in 2012) once pointed out: literary holidays are scarce on the ground. Shakespeare’s birthday tends to provoke global activity, and we often have literary festivals, but, as Sheffer says — and I can’t think of a phenomenon that contradicts him — there is only one annual commemoration of a fictional date: of a date on which something happened in a book.

When Flann O’Brien and John Ryan first set off on their pilgrimage in 1954, they took four friends with them. A.J. Leventhal – registrar of Trinity College — who, being Jewish, played Bloom; the literary critic Anthony Cronin, who played Stephen Dedalus; the poet Patrick Kavanagh, who played the muse; Flann O’Brien himself was Simon Dedalus and Martin Cunningham; while John Ryan was Myles Crawford; meanwhile, Tom Joyce, a cousin of James, played the entire Dedalus family. The men intended to retrace almost the entire novel, ending in Nighttown, but, by the time they arrived at Davy Byrne’s moral pub (only in the middle of Ulysses) they were, by all accounts tired and thirsty, so there they stayed, and the first Irish Bloomsday ended somewhat prematurely (Joyce, one feels, would have approved).

Our first Bloomsdayers were celebrating a work of fiction that they loved, of course, but they were also celebrating a work of fiction that was despised by the country in which they lived. To pay homage to the work of Joyce in 1954, work so openly critical of Irish religious life, was not only to celebrate a great artist, but also to add their voices to his in critiquing the Catholicism and nationalism crippling Irish culture. As the critic Matthew Spangler points out, the first Bloomsday must have seemed a radical and subversive act to conservative, Catholic and nationalist Ireland.

For the next 20 or so years, Bloomsday in Ireland remained a small-scale event, celebrated largely by Dublin's academics and literati. It was not really until the 1980s, and the 100th anniversary of Joyce's birth, that Bloomsday was rehabilitated as a holiday for all. Then, it lost the kind of political expediency with which O’Brien and Ryan imbued it, and gained another kind: a kind almost diametrically opposed to the first. Bloomsday now functions in Ireland as a sign of our state-sanctioned modern cultural identity.

Ireland in the eighties had been a member of the European Union for seven years, and, though more socially conservative than its European neighbours — with divorce illegal, contraception difficult to get, abortion illegal, homosexuality illegal, and with strong Catholic presence in most state funded institutions — it was in the process of improving its infrastructure, and embracing a globalized, industrialized economy. Suddenly it had reason to celebrate its great, worldy, modernist writer, and to put Dublin on the map as the home of visionary literary prowess. The Ireland of the eighties, struggling out of the shackles of theocracy that had defined its post-independence, wanted to celebrate not only it Gaelic roots, but also its modern genius. Joyce was finally welcomed home.

Dublin’s Bloomsday celebrations became characterized by re-enactments and performances, that tied the text to the city, and this, of course, attracted lots of literary tourists from around the globe. These performance-based public interactions with the text were also expedient in another way: they made Ulysses accessible — Bloomsday was no longer to be the prerogative of musty old scholars and high fallutin intellectuals: through performance and interpretation it could be enjoyed by everyone.

As Matthew Spangler again notes, the Bloomsday celebrations in Dublin: ‘function as a cultural performance that negotiates community through enactment.’ In other words, it brings people together. Irish identity is, in our time as in Bloom’s, in flux. Having a literary festival like this — so tied to Irish history, to Irish use of language, and to Dublin geography — is a way of creating and sustaining a modern identity in a time of change. And, as every national tourist board knows, nothing is quite as attractive as some well-packaged authenticity.

This might go a way to explaining why Bloomsday has become such a permanent fixture of Dublin’s summer calendar. But why, when walking in the geographic footsteps of Leopold Bloom is not a possibility, have enthusiasts instigated the holiday around the world, dragging friends along to evenings of reading in silly hats, and sometimes even sillier accents?

We can, of course, still answer this by alluding to the nature of Joyce’s text — having worked so hard to get into it, his readers simply don’t want to get out again. But we can also look at it through the lens of expediency to see what kind of wider social and political work it performs.

Well, a major and obvious reason for Bloomsday’s success is the proud Irish diaspora around the globe, who often participate in Irish cultural events like Saint Patrick’s Day to strengthen their sense of community or their cultural ties to Ireland.

Frances Devlin-Glass wrote an article on Bloomsday celebrations in Melbourne which highlights this. Of her 73 respondents from Melbourne’s Bloomsday going population, 53 per cent were Irish-Australian or Irish born, and only 31 per cent reported no Irish ancestry. Asked why they were interested in the works of Joyce, respondents’ first most common answer was his experiments with language, the second his humour, and the third, his Irishness.

Devlin-Glass also notes a strong sense of cultural purism regards Joyce on behalf of the Irish. The Melbourne Bloomsday celebrations have an emphasis on making Ulysses local — on drawing parallels between Melbourne and early twentieth century Dublin. The scholar’s Irish respondents were largely opposed to this practice, with one quoted as saying:

I cannot see how making Joyce "Australian" or any other nationality, works to extend Joyce. Its very centre is Ireland, the works are Irish. These are the core areas to understand in order to be able to appreciate, understand, and respect what Joyce is about.

Quite a long stretch then have we come from an Irish culture that would not recognize its salacious and ungodly son, to one that insists he is not befouled by other nations and cultures. And, in this purism, we must recognize a certain drive on behalf of the Irish to own Joyce’s considerable cultural capital, both at home and in diaspora.

But, of course, lovingly befouled by our globalized era will Joyce continue to be, with Bloomsday cut loose from the geography of Dublin, not only by diasporic celebrations, but also with the passing of years that has rendered our cityscapes so different to his. And though I have, throughout this talk, focused on the aspects of the celebration that are expedient — that have allowed Joyceans to make political statements, or cultural bodies to make the work accessible, or communities to come together, or Ireland to harness the global cultural capital that Ulysses represents, perhaps you’ll now permit me, like Molly, a breathier, fleshier closing remark.

Bloomsday has always been put to practical purposes, but whether we are by the Liffey or the Saint Lawrence, when we commemorate every base and sublime detail of a day that never happened we remind ourselves that our mundane existences are as ripe with sensuous experience, with unfinished thoughts, with undeciphered symbolism and ancient mythology as Bloom’s own.

Bloomsday commemorates our reluctant drudgeries and our small pleasures. In commemorating it, we commemorate nothing, if not ourselves.

The 2015 edition of Montreal's June 12-16 Bloomsday Festival is co-organized by Concordia's School of Canadian Irish Studies. Register now for dramatic readings, film screenings, pub quizzes and more.