For many, the expression refers to a person who donates large sums of money to causes like the arts or children’s hospitals. While Vadean doesn’t aim to downplay contributions like these, she hopes to expand the term’s scope.

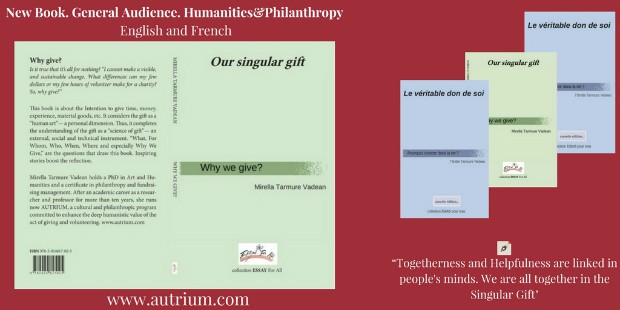

So when she says her new book Our Singular Gift. Why We Give? “is for anyone who is or wants to become a donor,” she means anyone who is willing to donate time, experience and knowledge to a cause, not just money.

In the book, Vadean explores the titular question, why people give, along with what constitutes a gift, and where a person’s generosity would have the most impact.

One section is devoted to proving the anachronism of the fundraising pyramid, which places large gifts at the top, ipso facto putting other people’s smaller but still meaningful contributions at the bottom.

Small gestures, big effect

One of the book’s anecdotes focuses on a taxi driver who’s dispatched to a seemingly deserted address. He wants to leave in a frustrated huff, but something compels him to go and ring the doorbell.

A frail old woman in a near-vacant apartment answers. He helps her to his cab, where she tells him to take the long way through town. This cab ride is her final victory lap: she’s on her way to a hospice to be bed-ridden.

After two hours spent revisiting her past, the cab pulls up at the hospice. The woman opens her coin purse to pay, but the cab driver refuses any money. “It was the most important thing I had done in my life,” he says.

According to Vadean: “Giving isn’t to be understood as an act. It’s a way of being. It is not what, or how much we give, which makes a difference, but how and what we feel when we do.”

A Concordia-inspired passion

Vadean has a wide and voracious appetite for learning. Before coming to Montreal in 2002, she earned a master’s in literature from the University of Toulouse-le-Mirail in France.

When she arrived in her new city, she began teaching French and, even though her previous degree was recognized, she applied to Concordia for a second master’s in literature. Once done, Vadean returned to Concordia in the individualized PhD program, specializing in the theory of imagination and perception.

“My time doing my PhD at Concordia was the best time in my life,” she says.

Vadean was an unusually active student. Among sundry other projects, she headed a research group that brought together colleagues from other major universities around the city.

Her tireless work paid off in a major way. Over the three years she spent completing her doctorate, Vadean received 14 grants and awards.

Mirella Tarmure Vadean is the author of Our Singular Gift. Why We Give?

Mirella Tarmure Vadean is the author of Our Singular Gift. Why We Give?

Our Singular Gift. Why We Give?

Our Singular Gift. Why We Give?