Late artist and high-school teacher surprises Department of Art Education with generous endowment

Campaign for Concordia donor, Rose Szasz, at her home on Île Bigras.

Campaign for Concordia donor, Rose Szasz, at her home on Île Bigras.

A multitalented artist and high-school teacher has empowered Concordia students with a surprise bequest of $95,000 to fund scholarships at the Department of Art Education.

The planned gift to the Campaign for Concordia was made by the late Rose Szasz, who succumbed to Parkinson’s disease in 2021. She was 86.

By all accounts, Szasz lived a fiercely independent life, replete with creativity and purpose.

The focal point for this was her modest but well-curated home on Île Bigras between the Island of Montreal and city of Laval.

Infused with unique charm, the community of 400 residents was where Szasz, a painter, sculptor and ceramicist, chose to make a life surrounded by books, plants and plenty of art.

After Szasz purchased her one-storey house in the 1970s, she had it raised and converted the basement into a studio. A separate workshop on her property contained a gigantic kiln where she fired her pottery.

“It was basically a summer cottage on cinder blocks before Rose had it lifted,” says potter Don Goddard, a friend and collaborator. “After the work was completed, the basement studio was flooded with natural light.

“She had a press and did printmaking, photography and etching. She was an accomplished watercolourist, and her drawings are among the best executed you will ever see.”

Szasz’s beloved cat was a favourite subject, as were frogs and a range of other animals. Scenes from Île Bigras, Montreal and around Val-David, where Szasz regularly exhibited, inspired her watercolours.

So, too, did her travels. “Pottery Market, San Miguel,” inspired by a trip to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, earned Szasz a silver medal by the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour in 2014.

Among some of her neighbours, Szasz was a subject of fascination.

“I was always curious to know what Rose was up to, but was too timid to approach her,” recalls Claudia Laurin, who grew up next door. “She would be in her studio at all hours.”

One of Szasz's many artworks.

One of Szasz's many artworks.

Laurin would later overcome her shyness to form a friendship with her neighbour, and even come to live in Szasz’s house after it was sold to Laurin’s father in 2019.

Laurin lives there with her husband and two daughters, and says that while the house had to be renovated to accommodate her family of four, she has done her best to preserve Szasz’s spirit through her Espace Musée de Rose, which is open to visitors by appointment.

“I have about 60-odd pieces from Rose, and many of her books and other personal effects as well,” says Laurin, a licensed occupational therapist who, as it happens, teaches art and has a master’s degree in museum studies from the Université de Montréal.

“In addition, Diadra Sherwin, a kind of niece figure to Rose, has contributed many photos and a lot of information about Rose’s life.”

‘Rose was fearless’

Born in Pécs, Hungary in 1935, Rose Szasz’s childhood coincided with what was arguably the most difficult period in the country’s long history.

Hungary faced formidable challenges, from Nazi Germany and the Holocaust to an authoritarian Soviet Union that brutally defeated a resistance movement in 1956.

As all of this unfolded, Szasz grew up poor and largely under the care of a single mother and foster family. Her creative talent was evident early on; she graduated from an arts-focused grammar school and later dabbled in photojournalism, a risky proposition behind the Iron Curtain.

“When she wanted to get her truck driver’s license, she had to train to operate heavy machinery and a firearm,” remarks friend and Île Bigras neighbour Margaret Jones. “Apparently, she was quite the markswoman.”

As Soviet oppression peaked in the late 1950s, Szasz planned her escape from Hungary.

“As Rose later explained it to me, soldiers invaded her dormitory and started to round people up,” recalls Jones. “She ran out the back door and went to the train station with a friend, only to find that the platform was packed.

“They made the sensible decision to go see a movie. When they returned to the station, everyone had been cleared out by the Soviets. Miraculously, they caught a train and were able to cross the border. Rose was fearless.”

Like thousands of her compatriots, Szasz found refuge at a displaced persons camp and made her way to Canada alone to start a new life in Montreal.

From Sir George to the University of Guanajuato

When Szasz showed up to an interview at Sir George Williams University — a decade and a half before it merged with Loyola College to become Concordia — she spoke neither English nor French.

Armed with her portfolio, she persuaded administrators like Douglass B. Clarke and Henry Hall — two of Concordia’s most prominent builders — that all she needed was a pencil and a paintbrush to study studio arts.

Szasz soon mastered a decent command of English and thrived on campus.

After a stint at Bell Telephone she completed a teacher’s certificate at McGill University, and was listed among the staff at Northmount High School (now Shadd Academy) in Côte-des-Neiges, Montreal, for both 1963 and 1964.

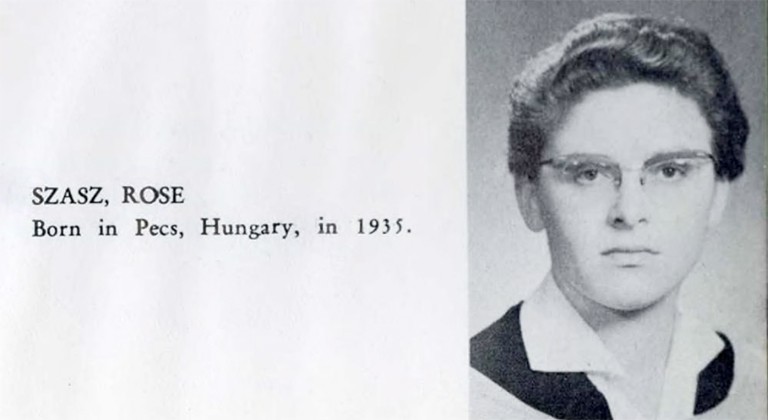

Szasz attended Sir George Williams University in the early 1960s.

Szasz attended Sir George Williams University in the early 1960s.

In 1966, she was awarded a scholarship by the School of Art and Design at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts to study under Arthur Lismer, the famed member of the Group of Seven. Szasz later earned her MFA from the Instituto Allende at the University of Guanajuato, Mexico.

Upon her return to Montreal, she established her career as an art teacher, the majority of which was spent at Riverdale High School in the northwestern suburb of Pierrefonds.

She also exhibited widely, most notably at the Canadian Guild of Craft in downtown Montreal, where she was honoured with an award for excellence in 1988.

‘The disease robbed her of her motor skills’

Szasz gave her last art class at Riverdale a decade later. In retirement, there was more time to create and to cultivate old and new relationships.

Two of her closest friends were Margaret Jones and her husband, Jon, both art collectors and teachers themselves (Jon, a carver and painter, taught at Riverdale with Szasz). A staff party at the couple’s Île Bigras home was what sparked Szasz’s initial enchantment with the suburban community.

Margaret and Jon, who served as executors of Szasz’s estate and who now live in the city, have fond remembrances of their time on the island with Szasz.

“Île Bigras was the kind of place where you could take a walk in the morning and not return until evening, having been invited to someone’s house for lunch, coffee and maybe even dinner,” says Jon. “It was neighbourly that way, which I think Rose appreciated.”

As Szasz entered her 80s, however, her health declined. After she collapsed in her yard one day, doctors discovered a heart malfunction and put in a pacemaker.

Then her Parkinson’s worsened.

“When we finally helped her decide to move to a special care facility in 2019, that was quite hard,” admits Margaret Jones. “But when the movers came to take her things, she was quite stoic about it, which I found rather incredible.”

With the loss of her way of life on Île Bigras, Szasz was also deprived of her ability to do what she loved best.

“That’s the cruel thing about Parkinson’s,” says Jon Jones. “The disease robbed her of her motor skills, though she did persist with her sketching for as long as she could.”

After two years at the care facility, Szasz died in September of 2021.

While there is no definitive explanation as to why she left such a large portion of her estate to Concordia, there are a few theories.

“Rose was the kind of art teacher who wanted her kids to explore their creativity unselfconciously,” says Don Goddard.

“She took pride in being a specialist and in mentoring younger artists.”

There’s another reason, too, adds Margaret Jones.

“Just think about how she grew up in Hungary, and the challenges she had to overcome,” remarks Jones.

“She was grateful for the life that she had built for herself as a teacher and an independent artist. I think Rose wanted to help others have that kind of life, too.”