Charlie Gedeon sits before a middle-aged man, opens his notebook and clicks his pen. He places an audio device in front of his subject and hits record. This interview is the first of many he will conduct for his latest project. But Gedeon isn’t a journalist. He’s a user experience (UX) designer set to develop a new medical app that monitors chronic kidney disease, which affects one in ten Canadians, and he’s speaking with patients to guide his work.

“I try to start at a bird's-eye view and build an image of the person’s life and goals, which have nothing to do with the app,” explains Gedeon, the co-founder of Pragmatics Studio, a design firm based in Montreal. “Apps are only a means to an end for a goal that someone is trying to achieve.”

Understanding the motivations and aspirations of users is a challenge for the world's UX professionals, a community estimated at one million in 2017. Through methods like user interviews, they attempt to understand the experience of others—or employ empathy—to deliver solution-focused products.

Trusting the user’s expertise

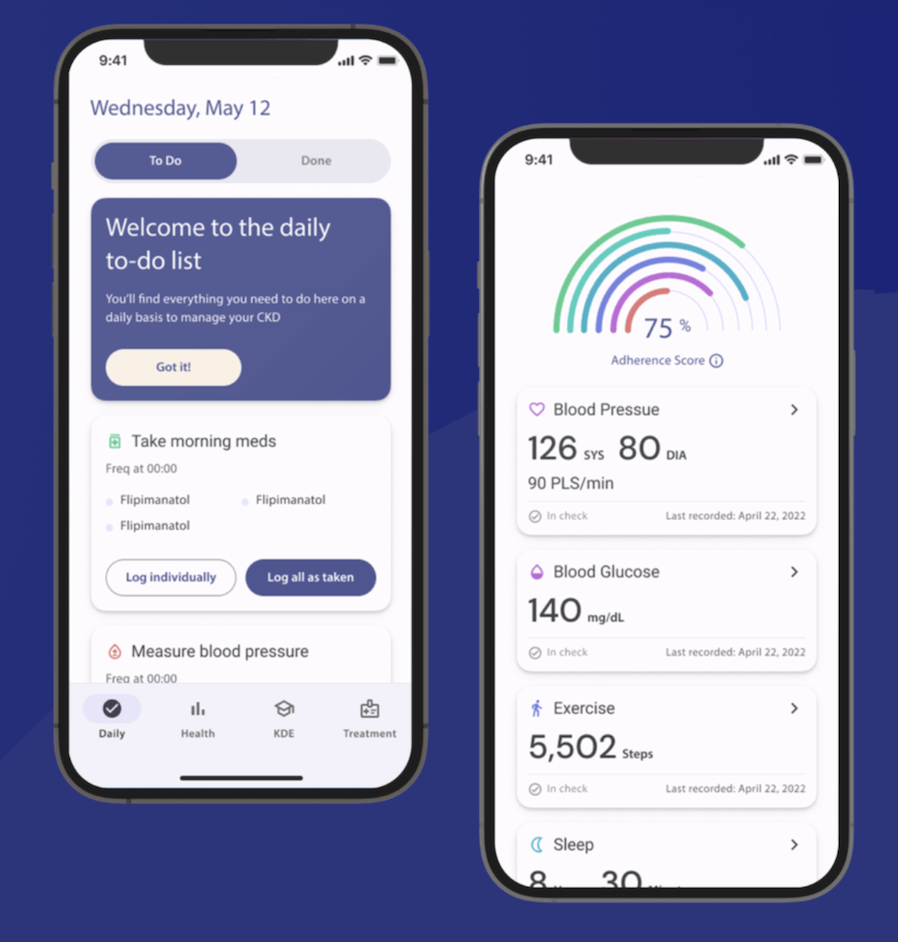

The medical app Gedeon worked on encourages users to input biomarkers to monitor their chronic kidney disease (CKD). His user interviews revealed that diagnosed patients struggled to keep pace with their treatment plan since it requires daily vigilance in managing diet, medication, and health metrics. In response to this finding, Gedeon and his team tweaked the app’s design. They shifted from an educational model where users scour for information to guide their daily treatment, to one that provides clear instruction about the biomarkers they need to measure, like blood pressure and blood sugar levels.

This modification was rooted in the user-centred approach known as empathetic design.

“Kidney disease impacts their life, but they’re not defined by it,” notes Gedeon. “We needed to respect their time, so we decided to approach it like it’s one of the other tasks in their day, just like buying bread and checking it off their list.”

The World Health Organization estimates that in developed countries, just 50 per cent of patients with chronic diseases, including CKD, adhere to their treatment plans. During his interviews for the app, Gedeon met a patient who was successful in combatting this rate by using paper and phone reminders. This insight led Gedeon and his team to consider gamifying the user’s experience in the form of a to-do list that delivers positive reinforcement upon completing each task.

“Our job is to take the pains, but also sometimes take the things that are super insightful,” notes Gedeon. “Rather than empathizing with someone’s pain, we can flip the interview and think of the user as an expert, and that could inspire our solution.”

Medical app display

Medical app display

UX designer Charlie Gedeon

UX designer Charlie Gedeon