MIKA YATSUHASHI

An Uninterrupted View of the Sea

2020

Video, 15 min, 8 sec.

Artist statement

Using old photographs, Super 8 film and FBI documents, a Japanese-American filmmaker tells the story of her family’s struggle to prove their American identities during World War II. From his art dealership to his beloved beach house, the filmmaker’s great-grandfather is subject to suspicion. Standing in flux between the identity of “alien” and “citizen,” Mika Yatsuhashi explores the effect of her family’s Japanese immigrant history on her American identity today.

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Artist’s biography

Mika Yatsuhashi grew up in Takoma Park, Maryland. She moved to Montréal in 2017 to attend the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema at Concordia University and graduated in 2021 with a BFA in film production. In 2020, she won the Mel Hoppenheim Award for Outstanding Achievement. She has a passion for exploring documentary film, identity, and American history, as well as working with archival material. Her film, An Uninterrupted View of the Sea is her first to be released nationally and internationally, with screenings at HotDocs (Toronto), Rendez-Vous Quebec Cinema (Montreal), the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Museum (Washington, DC), and more.

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Essay

A Rude Awakening: The Myth of the American Dream

Author Anastasia Koutsogiannis

Artist Mika Yatsuhashi

Artwork An Uninterrupted View of the Sea, 2020

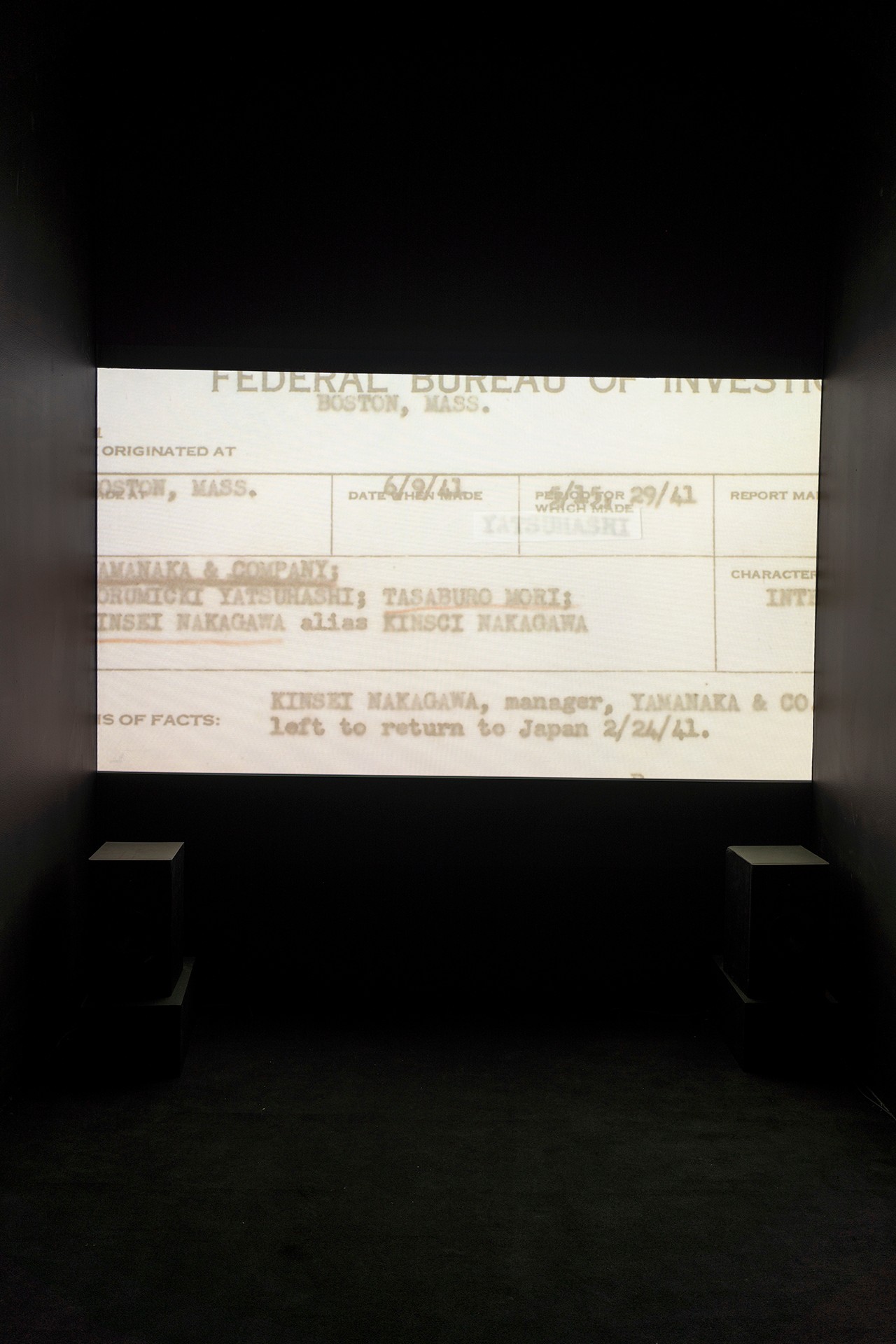

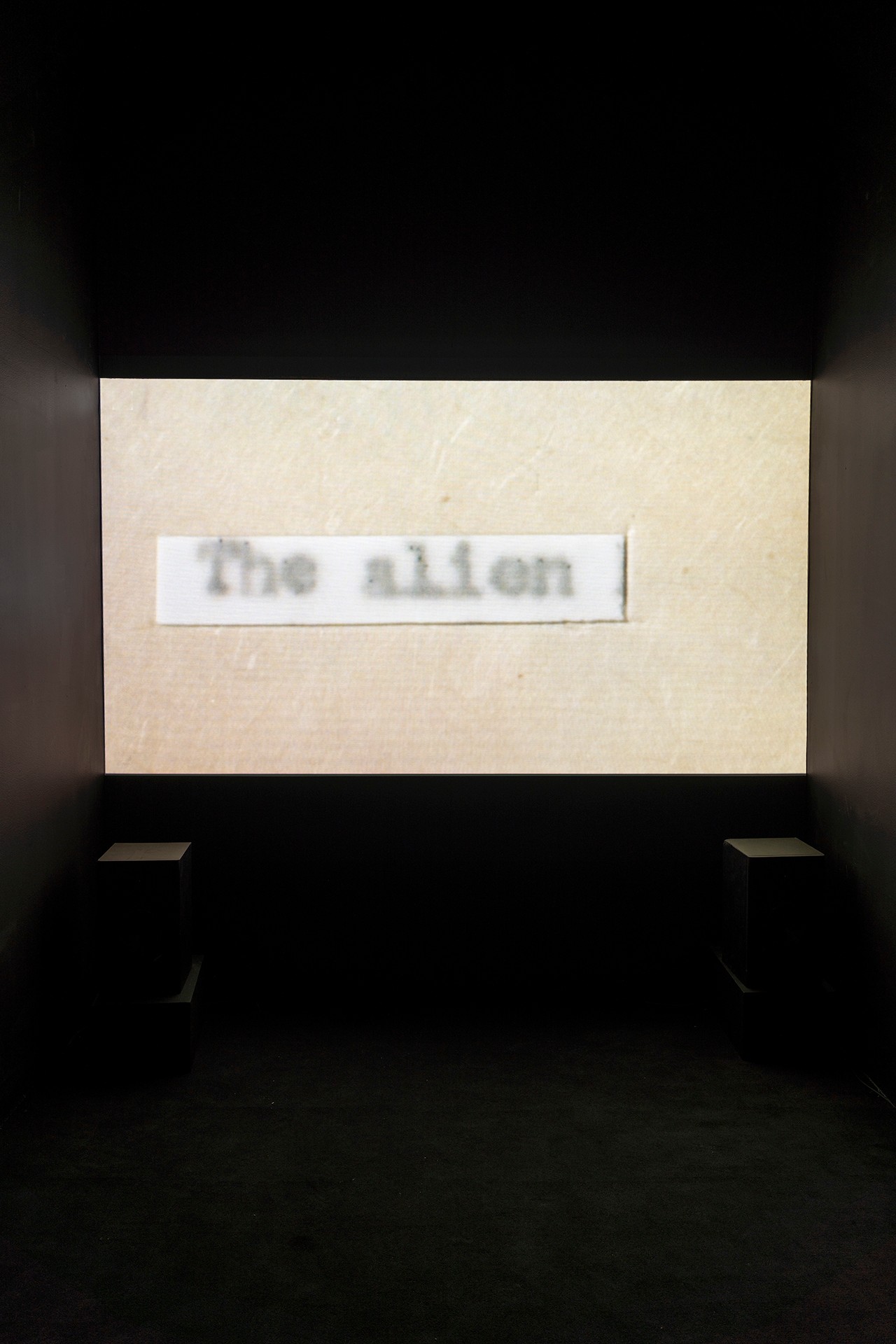

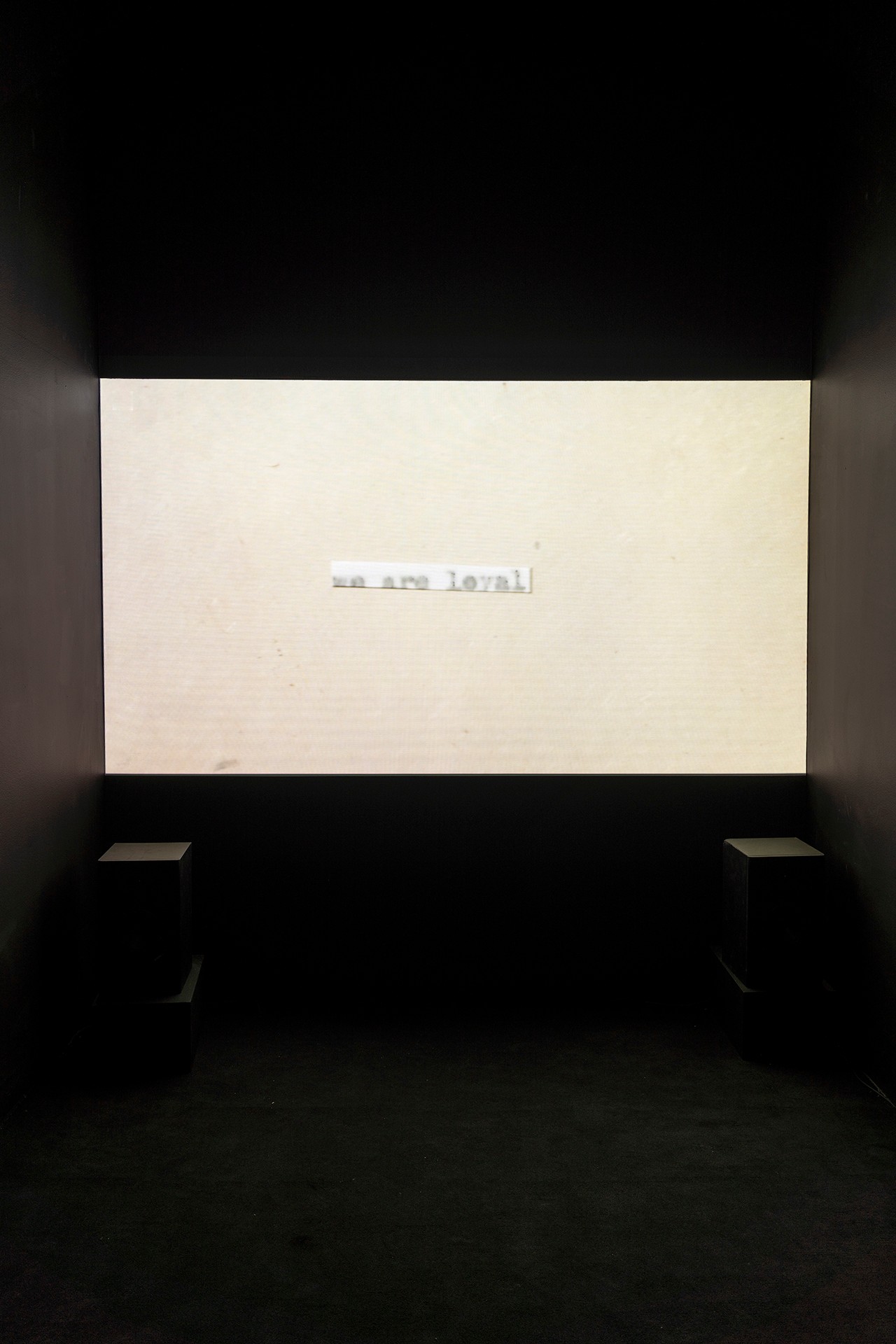

What does it take to be considered a true American? A few years before the eruption of World War II, the United States put together custodial detention lists of Japanese-Americans across the country. Should war occur, this list would be used to gather anyone who the federal government thought suspicious. After the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, the names on those lists were deemed as “enemy aliens.” The Japanese community in the U.S. underwent surveillance, with many being forced into army-run internment camps.1 A testimony to these disturbing times, Yatsuhashi’s film An Uninterrupted View of the Sea explores the experience of her great-grandfather, Haruchimi Yatsuhashi, a Japanese-American. Having arrived in 1907, the young businessman settled in Boston as the respected vice-president of the notable art company Yamanaka and Co. After years of contributing to society Yatsuhashi was met with suspicion and investigations. Grappling with familial archives, the perfect American life reveals itself to be completely false.

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

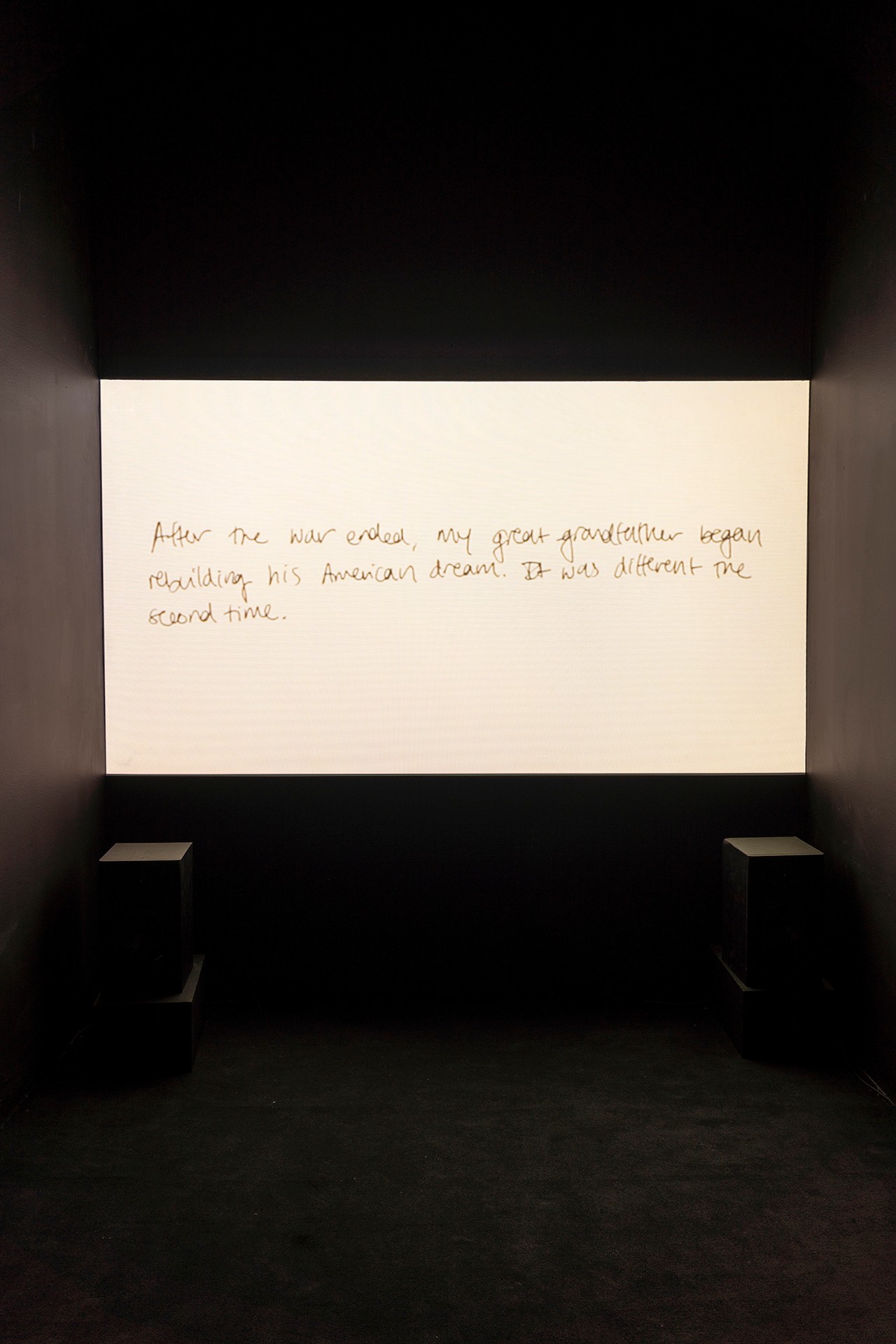

Settled into the gallery’s immersive Black Box, scenes of nostalgia and happy recollections travel across the screen. Despite the sweet moments, a palpable tension looms. As the FBI’s cold words sweep across our view, the filmmaker reveals her hands and voice as a guide to her family’s past. Yatsuhashi has explained the significance of her formal choices: “My goal with the cut-outs was to have you read them as I read them : with laser focus and with specific attention to the language.”2 Through this, the filmmaker allows us to experience the deconstruction of the document just as she did. Sharp, mechanical words and sounds oppose the summer joy as the federal documents seep into the reverie. At the hands of a systemically racist operation, an “uninterrupted view of the sea in either direction” became a suspicion. The filmmaker shared, “even if you [an immigrant in America] succeed as much as possible, you can still get knocked down.”3 This sort of system is impossible to defeat. For the Japanese-American community, their “Americanness” is given and taken away as society wishes. No matter how far one climbs the social ladder, instability is a looming and large presence.

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

What happened to them is like the worst nightmare for a lot of immigrant families.

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

The disregard toward Japanese traditions and cultural legacies also furthered unwarranted isolation. On the screen, archival images from Yamanaka and Co.’s inventory appear before us and disappear just as quickly. Lost to public auctioning, the rich contributions of the Japanese-American community, and more specifically the Yatsuhashis, are devalued and dismissed. “What happened to them is like the worst nightmare for a lot of immigrant families. For America, the culture is you come, and you assimilate if you want to succeed. A lot of times you’re forced to, or you feel the need to abandon a lot of ties to your home country.”4 Reflecting on our conversation, the artist concluded, “If you want to identify as an American you need to define that for yourself and come up with your own standards.”5 By uncovering her family’s history, Yatsuhashi’s film speaks on the widespread journey toward acceptance, ultimately found to be set up for failure. After all these years, the need to be embraced is met with opposition from those who offered the challenge in the first place.

- Densho, “Looking Like the Enemy - Densho: Japanese American Incarceration and Japanese Internment,” accessed on July 10, 2015.

- Mika Yatsuhashi in conversation with the author, June 2021.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Author’s biography

Anastasia Koutsogiannis is a Montreal-based Art History and Film Studies student at Concordia University. Interested in connecting with artists of every style and medium, she joined the online art market and community Bidgala, as a member of their editorial team. Through her writing, she aims to enhance creators’ voices through a diligent analysis in hopes of interweaving their pieces into the written world. She believes there is an importance in documenting and anchoring the memory of art pieces; whether it be through paper, photographs, the Internet, and everything in between.

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux

Photo by Guy L’Heureux