Harmony of Sorrows: Collective Grief Across

by Kioni Sasaki Picou

Somaye Farhan, This is not a scarf.

Somaye Farhan, This is not a scarf.

Maya Gilmour, This Was a Home

Maya Gilmour, This Was a Home

Em Laferrière, Ambigü

Em Laferrière, Ambigü

In a world where loss is common, healing is perpetual. Despite the direness of these collective experiences of loss, we are privileged to witness the personal narratives of three artists, Somaye Farhan, Maya Gilmour, and Em Laferrière, in pursuit of their healing journeys. In a time when colonial structures are still prevalent, it is alarming to witness the ongoing complicity of the “Global North” in armed conflicts and ethnic cleansing abroad. The violence of colonial powers in the “Global South” causes unbearable distress and overwhelming grief which the diaspora is expected to suppress at the comfort of the “Western’s” consciousness. Stuck between the current colonial hold and capitalistic obsession, the ones who are the most affected are rarely granted a moment to acknowledge feelings of loss and empathy. In their works, all three artists manifest their processes of evolution—some out of survival, some to cope—through the stillness of reflection and growth.

The installation, This is not a scarf, conveys a powerful message about resistance in the face of oppression, through the symbolic significance of the compulsory headscarf in Iran. Triggered by the outburst of protests following the death of Mahsa Amini in Iran in 2022, Iranian artist Somaye Farhan employs performance, sculpture, and installation to explore the misogynistic ideals imposed on women and girls by the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran. In her work, the artist speaks to the external forces that constrain the movements and agency of feminine bodies. After the 1979 Iranian revolution, a conservative version of Islam was adopted by the government, leading to increased gaps in gender equality. Laws were put in place regarding strict veiling, clothing, and women’s participation in certain professions and activities. Over the past 45 years, Iranian women have fought to address these inequalities and demand change. Those of us with the privilege of freedom are called to support emancipatory movements and extend our power towards solidarity and visibility.

At the heart of Farhan’s installation, a cast bronze pair of hands, molded from the artist’s own hands, is bound by a scarf, resembling shackles. A video documenting the artist’s collaborative performance with artist Elahe Moonesi in October 2022, contextualizes the sculpture. The performance piece included participation by spectators, who were granted the power to place headscarves on the performers, Farhan and Moonesi, and to reflect on recent events in Iran. This piece contemplates how sharing our lived experiences during traumatic events allows for bonding within communities through processing these events and fostering the resiliency to move toward healing. Each scarf was donated by an Iranian woman based in Montreal, making their contribution an “integral part of the artwork.” i A selection of headscarves, adorned with screen-printed messages collected during the performance are featured in the York Vitrines, alongside the sculpture and video. The artist’s collaborative work encapsulates the harsh realities for women in Iran by manifesting a space to both memorialize those who suffered or perished through state-sanctioned violence and those who survived and are still standing up against the government. As it is a risk to not wear a hijab in Iran, This is not a scarf exposes the way in which this object has manufactured political and social invisibility, in the Iranian context.

The installation initially appears as a commercial display, reminiscent of the vibrant scarf shops in Iran.ii However, it challenges viewers to question its true nature as an artwork, as upon closer examination, the underlying narrative of resistance and oppression emerges.iii The scarf’s role undergoes a transformation when viewed from different perspectives. While acknowledging the severe enforcement, it’s crucial to recognize that for some women, the decision to wear the hijab is empowering. Rather than solely emphasizing the act of choosing self-expression, it is pertinent to highlight instances where the choice is constrained, where one is compelled to decide in relation to one’s freedom rather than personal expression.

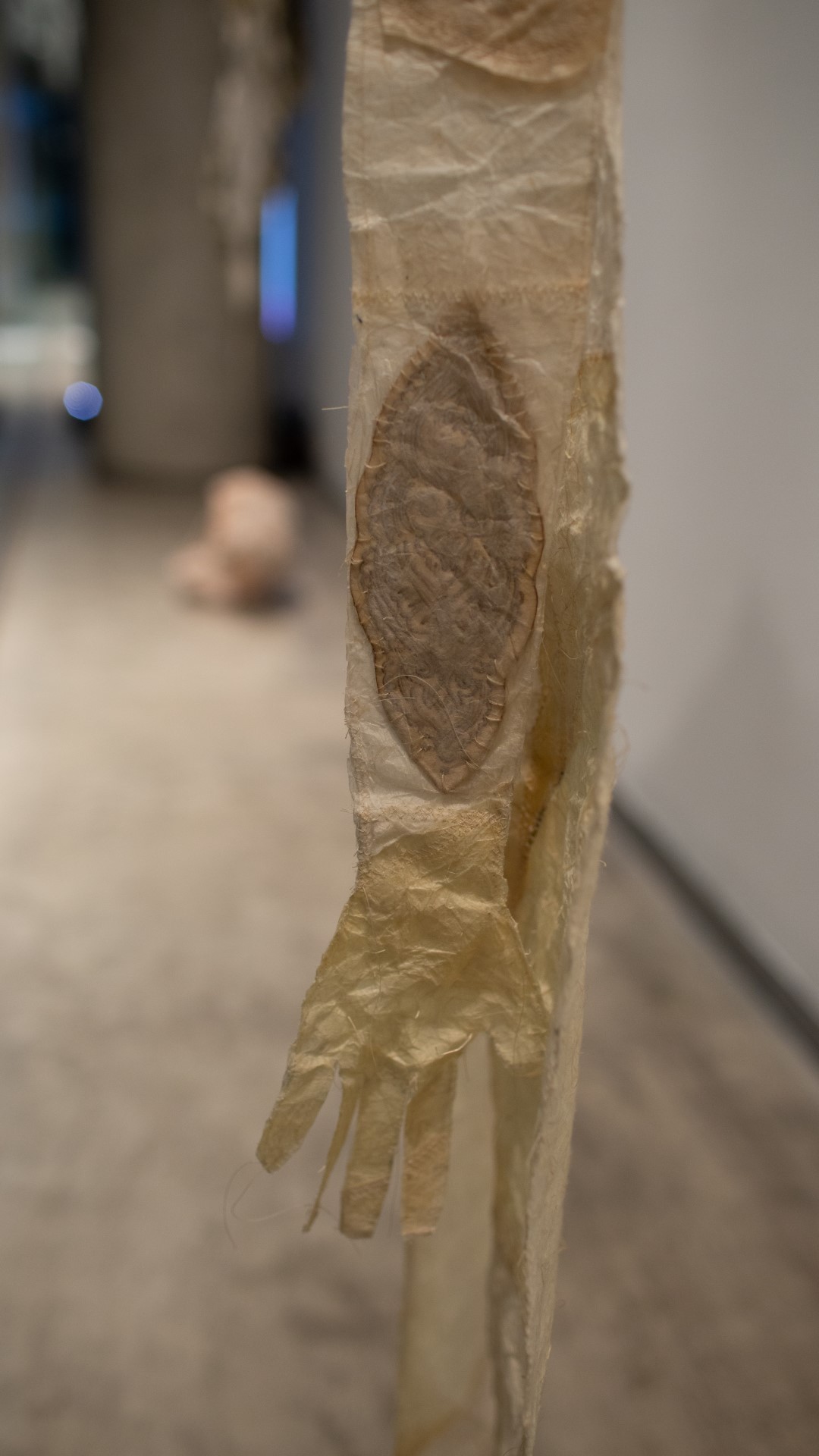

In contrast to Farhan’s piece, Maya Gilmour’s This Was a Home and Peau Fantôme are two contemplative installations delving into the themes of healing and grief through the transitional nature of corporeality. The pieces examine the idea of the body as an empty vessel, echoing the presence of those who have inhabited it before, which, much like a shell or a carcass, retains imprints of its past experiences, growth and changes. Gilmour uses fabric strong enough to hold on its own while keeping traces from its past usage; it takes on shapes and colours as if it has been already inhabited. The material resembles “peeling glue from the fingertips…imprinted with the past.” iv

The artist’s exploration catalyzes cycles of transformation and provides a vessel for memories, including moments of touch, labour, trauma, and recovery. In our day to day lives, we inevitably evolve and become the amalgamation of our history. Grief, in this context, becomes a part of the larger narrative of life’s changes and transitions. Healing is found in acknowledging and preserving the essence of what once was, even in its absence. In this work, Gilmour honours her past selves while inviting the public to contemplate their own cycles of shedding and renewal.

Similarly, Ambigü reflects on grief for our past selves while still acknowledging them to being a part of who we are today. This work by Em Laferrière seeks to guide viewers on a reflective journey that challenges outdated notions of gender identity and performance.v Despite its evocative nature, this work is intended to facilitate healing and community connections. It features larger-than-life photographic portraits of transgender men at various stages of their gender affirmation journey with dimensions reaching up to 40 x 60 inches, to maximize the impact on the viewer. Aiming to destigmatize and normalize the transgender experience, these images counter the objectification and social exploitation faced by members of the trans and gender non-conforming community. Through this photographic series, the audience witnesses a process that is heavily stigmatized. Because many remain uneducated about trans issues, the misconceptions around members of this community often reduce them to commodities rather than complex individuals with agency over their bodies. The presence of the artist’s sitters asserts their right to claim space. By positioning the body next to a natural environment, the artist creates an immersive landscape where bodies of all kinds are portrayed as being “found in nature.” vi Laferrière insists these bodies are not “unnatural” —a common transphobic argument —rather they are a natural element of a person's identity.

Ambigü navigates the complex emotions of grief experienced by the transgender and gender non-conforming communities in the face of ongoing discrimination and marginalization. With over a hundred anti-trans bills passed at an unprecedented rate, access to health care, education, and public spaces have increasingly been targeted. Not only is this a tactic of erasure, but these bills also represent an attempt to exert control over movement and representation and perpetuate anti-trans ideologies. Since not all people are protected by the same rights in North America, the intersection of trans identities and racial identities can bring on more violence and oppression, particularly for Black trans women.

In some schools, conservative policymakers have gone as far as banning queer “behaviour” on their premises, communicating to children that queerness is not an acceptable way to live while damaging young queers’ self-esteem and encouraging transphobia. This dehumanizing lens exposes queer and trans students to violence and societal and economic inequality. The series promotes self-empowerment and the creation of spaces where diverse bodies and identities are celebrated and normalized, while challenging white cis-gendered heteronormative stereotypes. As Laferrière states: ”This series is not only an act of resistance but an act of repair.”vii

Em Laferrière, Mountains (from the series Ambigü), 2023, vinyl, 60” x 40”. Photo credit: courtesy of the artist

Em Laferrière, Mountains (from the series Ambigü), 2023, vinyl, 60” x 40”. Photo credit: courtesy of the artist

With diverse approaches to addressing collective grief and healing, Somaye Farhan, Maya Gilmour, and Em Laferrière all engage with personal forms of mourning while also addressing how collective experiences of grief affect individuals. Whether it be through reflection on what once was, the acknowledgment of one's existence, or community organizing, they all parallel each other. Through this lens, each piece invites the public to understand other individual experiences or to find comfort with similar experiences. To consider where one may fit within grief, one must be allowed to honour the communities that are not granted the freedom to grieve in the public sphere.

Throughout all the works, the artists give voice to their processes of healing and transition. The works emphasize the need to acknowledge the past and present to foster a better future. With continuous news of conflict distributed on every platform, we become increasingly desensitized to human crisis, as we collectively cope with overwhelming and unprecedented violence, oppression, and guilt.

Oversaturated with so much misfortune, how does one engage with grief, if there is even time for it to exist? It is crucial to sit down with ourselves to reflect on why it is easier to disengage and disconnect. Whether through literature, art or other expressive media, engaging with these works allows individuals to pause, reflect, and navigate their emotions in a meaningful way. By fostering a sense of connection, understanding and shared humanity, these narratives contribute to a collective journey towards healing. In recognizing that others grapple with similar challenges and emotions, individuals can find solace in collective understanding.

[i] Somaye Farhan, This is not a scarf, artist statement, 2023.

[ii] Ibid

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Maya Gilmour, This Was a Home, artist statement, 2023.

[v] Em Laferrière, Ambigü, artist statement, 2023.

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Ibid

About the author

Montreal-based photographer and co-editor-in-chief of arts and culture publication, SUKO, Kioni blends her Japanese and Trinidadian heritage with a passion for decolonial art practices and community building. She works to challenge societal norms and amplify the voices of marginalized communities, aiming to expand spaces for those misrepresented by major narratives in art history. Kioni's commitment to compassion and understanding in her artistry catalyzes social change, fostering empathy and solidarity through visual storytelling.