Red.Chewy. Faint notes of cinnamon laced with despair, and moths.1980.

by Nico Linh

Lucy Gill, Mastication

Lucy Gill, Mastication

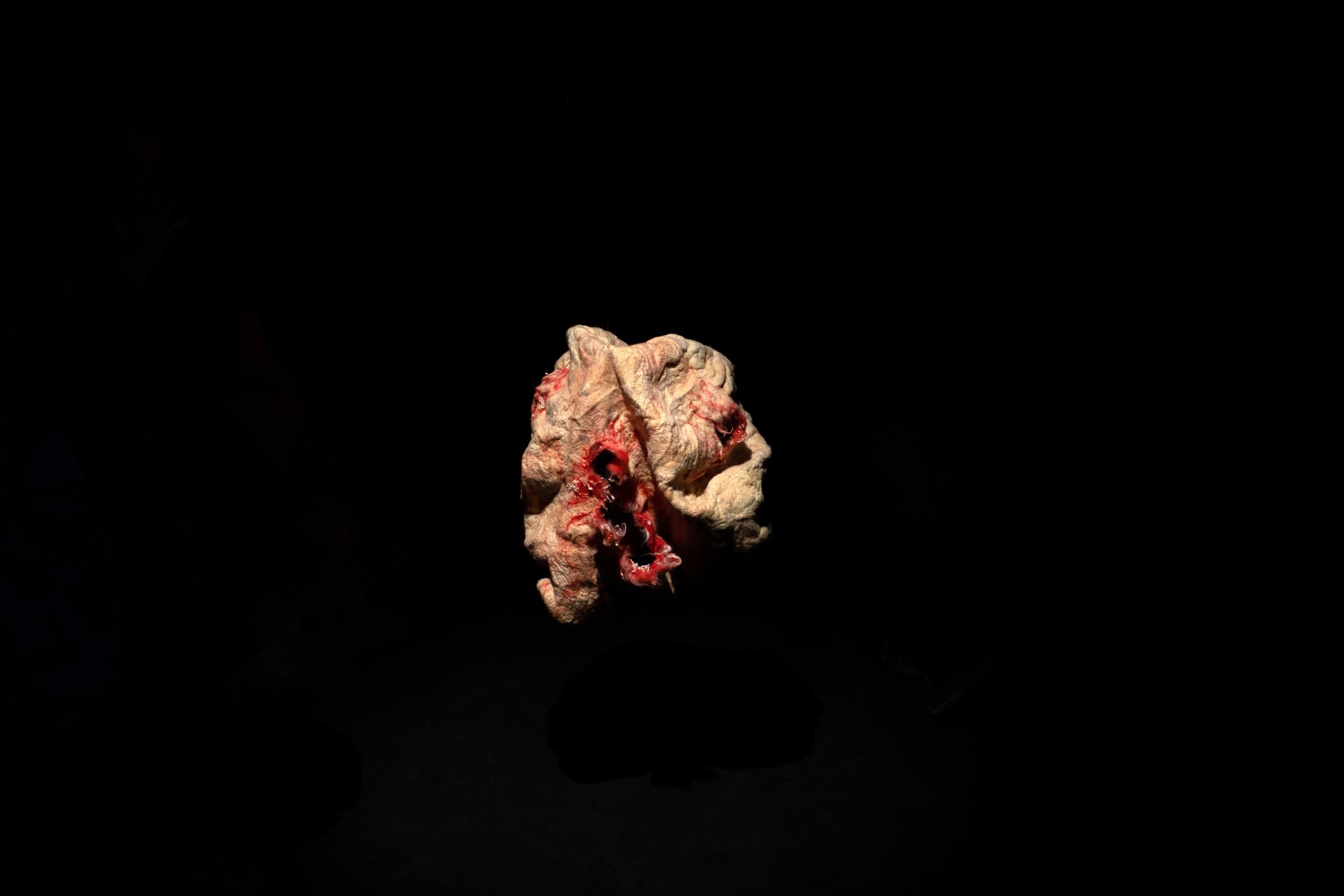

Emma McLean, An Invitation to Touch

Emma McLean, An Invitation to Touch

Levana Katz, Everything is Muscle and Exists

Levana Katz, Everything is Muscle and Exists

In the folds of malaise and confusion, Lucy Gill’s Mastication, Emma McLean’s An Invitation to Touch, and Levana Katz’s Everything is Muscle and Exists upend the familiar through the act of queering the body. Queer, as in non-normative, as in being at odds against one’s surroundings, as in directionless, disoriented, a limbo and an inhabited corpse. Through the use of horror, each work engages in disorienting volleys that enable a deeper introspection about the limits of our bodies and their surroundings.

Lucy Gill, Mastication, Apple fruit leather, steel, 5,2”x 18”x 30”. Photo credit: Josh Jensen

Lucy Gill, Mastication, Apple fruit leather, steel, 5,2”x 18”x 30”. Photo credit: Josh Jensen

An eerie silence imbues Lucy Gill’s Mastication. A thin leather veil lays draped over a steel frame. Under the light, the leather’s colours change in hue, offering fleshy colour gradients akin to that of cured meats. Examining the leather surface, one can see that each patch is sewn to one another, the threadwork similar to that of sutures. The work’s sheer size, human-like in proportion, beckons the viewer to entertain a morbid thought: What if this were made of human skin? The idea leaves nothing close to plausibility, perhaps an intrusive thought brought by the dissemination of horror movie tropes. Something, be it the tiniest of doubts, seemingly gives it float. The morbid thought seeds itself and slowly creeps inside the visitor’s mind. Yet the familiar aroma of apple and cinnamon wafting through the air alleviates the malaise, hinting at the fact that the materiality of the work might only be fruit leather. A steel pedestal stands next to the drapery, and in a delightfully masochistic approach, the viewer is offered a piece of fruit leather to taste. Whether one indulges or not, the moment asks us to critically confront the malaise felt when experiencing the work. In a manner that could be reminiscent of consuming the body of Christ, the viewer must eat the jerky to confirm the materiality of the work, and only then can they feel relieved. Yet if the invitation of consumption is ignored, if the act is seen as too sacrilegious, then the visitor must sit with the thought, ruminate in its wake, and arrive at their own conclusions. Mastication plays with the familiar, that which is already known, using differing textures to subvert the already established, to disorient the viewer. Sara Ahmed quotes in Queer Phenomenology Heidegger’s concept of orientation, the ability to metaphysically direct oneself:

For Heidegger, orientation is not about differentiating between the sides of the body, which allow us to know which way to turn, but about the familiarity of the world: “(...) Familiarity is what it is, as it were, given, and which in being given ‘gives’ the body the capacity to be orientated in this way or in that. The question of orientation becomes, then, a question not only about how we ‘find our way’ but how we come to ‘feel at home.’”i

All matters of orientation must take root somewhere, in a solid point of reference to not get lost. In viewing Gill’s work there is seemingly no ‘home’ to go back to, no sense of normal, no objective place to secure oneself. The limits of the body are queered when confronted with the leatherwork’s uncanny resemblance to human skin.

Emma McLean, An Invitation to Touch, Merino wool, 4'5" diameter. Photo credit: Laurence Poirier

Emma McLean, An Invitation to Touch, Merino wool, 4'5" diameter. Photo credit: Laurence Poirier

Conversely, Emma McLean’s work, An Invitation to Touch lulls you with its soft woolly exterior, the dim lighting of the Black Box drawing attention to the floating mass. However, its amorphous shape violently thrusts the viewer into the same malaise as felt in Gill’s work. Cables spur from the ceiling above, pulling on the mass, tensing it. The mass folds in and exposes itself into a jagged, misshapen organ. The blob of wool has certain fleshy qualities to it: the pinkish tone akin to pigskin and the bleeding red tears reveal crimson insides as if something had just ripped it wide open. An Invitation to Touch indulges in the deformation and presentation of a corpse, ripping the visitor from their body. For the corpse is no longer part of the self, it is now waste strung up by cables, the presence of death within one’s body, in biblical terms: a body without a soul. With an already grotesque appearance, what would one find were they to peek inside the mass? To peer inside its dark maws, one would need to confront an ominous sensation to penetrate the work’s soft shell.

The epidermal can be seen as the first point of contact, the body’s first receptor of touch. One might feel around the woollen exterior before gathering the courage to reach inside, the unknown slowly diminishing as one’s hand feels. The grooves, the bumps, the fuzziness, everything is felt through the skin and processed as the mind identifies familiar sensations held within. At the same time, the woollen mass responds, touching back and leaving impressions on the visitor’s skin. The skin is not selective, it merely receives and “functions as a social membrane that renders the body vulnerable and susceptible to otherness, porous and open to what could count as ‘self.’” ii We are constantly exposed to external stimuli, and, with or without noticing it, our perceptions and bodies are repeatedly shaped by these encounters, these impressions. The constant stimuli create patterns through repetition, giving a semblance of order and structure fashioned into norms and standards. We can thus perceive ourselves as products of an intermingling between the self and the other, both interconnected and unable to exist independently.

Lucy Gill, Mastication, Photo Credit: Josh Jensen

Lucy Gill, Mastication, Photo Credit: Josh Jensen

Emma McLean, An invitation to touch, Photo Credit: Laurence Poirier

Emma McLean, An invitation to touch, Photo Credit: Laurence Poirier

Mastication and An Invitation to Touch both present elements of interactivity that establish an uneven power dynamic with the visitor. The visitor believes to have control, when in reality their agency is muddled by the disorienting nature of the works, control is inadvertently given over to malaise. Inside the realm of horror, discomfort plays a vital role as it functions as a way of signalling that something is wrong. The lingering feeling of something being amiss, this sense of lack, is explained through the abject. The abject is by definition undefinable, for it is “the place where meaning collapses on itself, the place where [‘one’ is] not.” iii Gill and McLean seemingly use the abject in order to estrange the viewer from their body, to remind them that they do in fact have a body, exteriorizing it, reducing it to inanimate flesh. Amidst the nausea, at the brink of abjection, when the mind breaks the body down into oblivion, a multiplicity of new possibilities can emerge. If one is able to be disoriented, then one is also able to be re-oriented, to be impressed upon. The norms and regulations previously imposed on the body are put into question and made anew.iv The loss of direction enables one to pursue new directions, subsequently fashioning unexplored ways of perceiving, which is in turn influenced by others.

Levana Kats, Everything is Muscle and Exists, Lithography, cyanotype, digital printing on Kozuke paper, MDF wood panels, glue, cotton thread, 4 pieces that are 21” x 16” x 3”, one piece that is 25” x 21’ (unfolded). Photo credit: Josh Jensen

Levana Kats, Everything is Muscle and Exists, Lithography, cyanotype, digital printing on Kozuke paper, MDF wood panels, glue, cotton thread, 4 pieces that are 21” x 16” x 3”, one piece that is 25” x 21’ (unfolded). Photo credit: Josh Jensen

Pulling from lived experience, heritage, and familial stories, Levana Katz weaves herself into a folded display of worldbuilding in Everything is Muscle and Exists. Printed paper panels are placed around a folded paper sculpture, acting like windows into another world. Inhabited by colonies of insects, this fabricated world presents glances of Katz’ introspection and orientation within her own microcosm. The centerpiece of Everything is Muscle and Exists is a folded paper sculpture. The sculpture can be manipulated and reshaped, folded into itself to contract and extend outwards like a caterpillar. The work lives, like a giant organism, it collapses and tenses like a system of muscles. Muscles in their physicality, hold memories and flex accordingly. After all, memories are spectres, haunting our bodies, pressing themselves against the glass front of our eyes, tinting each and everything that is perceived and orients the self. Cyanotype-dyed and lithograph-printed squares of paper are sewn together, white cotton threads in the shape of tendons lace around the squares’ extremities and hold them together. Though the tendon-like qualities of the threads are invisible when incorporated into the paper, the simple matter of it being there is enough to fuel the imagination and start our own narrative. On each square’s surface/skin appear alternating prints of moths, beetles, and grasshoppers among many other critters as well as distorted Hebrew characters pulled from the literary passage Katz had found in her mother’s research on Hebrew calligraphy: “Everything is muscle and exists.” Katz selects and physically imbues Everything is Muscle and Exists with her experiences and memories, for, as Mieke Bal states in Acts of Memory, “memory is something we do, not a passive recurrence.” v The process of creating the sculpture can thus be seen as an intimate process of worldbuilding. Every woven thread is a narrative, every folded crease is a page turned, every flexed muscle is an act of memory. Katz creates and finds her home, the familiar, amidst these insects, amidst warped Hebrew letters, amidst personal memories and family ties that end up shaping not only Everything is Muscle and Exists but themselves.

These acts of worldbuilding are sacred in shaping one’s perception, they create truth to solidly ground oneself, yet they are never absolute. Moments will come when this certainty will be challenged, moments felt when viewing Lucy Gill’s Mastication or Emma McLean’s An Invitation to Touch where the familiar body is upended and queered. Abjection petrifies, yet one must chew on the abject, dwell in its affection to then re-orientate oneself towards different directions. From the impressions left upon one’s skin, new worlds emerge where a sense of familiarity can be built, much like in Levana Katz’ Everything is Muscle and Exists. Like molting one’s own body away, leaving a stagnant carcass behind, we grow into new skin, new bodies, and new shapes to incorporate the vastness of life. It all seems cyclical, futile even, to engage in this process of loss and reconciliation of the self, to indulge in the horrors of the abject. Yet in these moments of respite, when everything suddenly clicks into place, when the tip of your fingers hunger in anticipation, when your eyes incandescently widen, when your ears attune to the harmonies of your soul; home is found.

[i] Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology (Durham: Duke University Press), 7.

[ii] Vivian Huang, Surface Relations: Queer Forms of Asian American Inscrutability (Durham: Duke University Press), 79.

[iii] Barbara Creed, The Monstrous Feminine (London: Routledge, 1993), 9.

[iv] Vivian Huang, Surface Relations: Queer Forms of Asian American Inscrutability (Durham: Duke University Press), 79.

[v] Mieke Bal, “Acts of Memories,” in Of What One Cannot Speak (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 218.

About the author

Nico adores a warm cup of tea on a snowy day. Perhaps one day, they’ll get to open a gallery for their friends, but that will have to wait after they graduate from Art History. For now, writing and enjoying what’s around us will do.