Groundbreaking exhibition co-curated by Concordia’s Heather Igloliorte celebrates past, present and future Inuit art

Among the wide range of Inuit art on display for the exhibition INUA, for curatorial lead Heather Igloliorte, one piece in particular stands out: a caribou hide bag with beadwork, made by her grandmother, Inuit seamstress Susannah Igloliorte.

The INUA exhibition was part of the virtual launch Qaumajuq, Winnipeg’s new centre dedicated to Inuit art and culture, that took place today and yesterday.

The bag came into Igloliorte’s life thanks to a chance encounter.

“Someone reached out to me on Twitter and said, ‘Hey, I think I have something that your grandmother made that my father bought and has been passed down in my family,” says Igloliorte, Concordia associate professor of art history and Tier 1 Concordia University Research Chair in Circumpolar Indigenous Arts. She was also on the 2012 Inuit Art Task Force that helped guide the planning of Qaumajuq.

“She passed away when I was a little girl, and so I didn’t get to spend as much time with her when I was growing up as I would have liked. So it’s really special to me to have this in the exhibition,” Igloliorte says.

INUA is a history-making show. As the first to be held at Qaumajuq, the new centre at the Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG), INUA features approximately 100 works from over 90 Inuit artists from across northern Canada, as well as some in the urban south and from circumpolar Indigenous artists.

The exhibition was curated by an all-Inuit team that represents the four regions of Inuit Nunangat, the homeland of Inuit in Canada: Igloliorte (Nunatsiavut), Krista Ulujuk Zawadski (Nunavut), Kablusiak (Inuvialuit Nunangit Sannaiqtuaq) and asinnajaq (Nunavik).

Heather Igloliorte: “We want Inuit to see this is an exhibition that is for them.”

Heather Igloliorte: “We want Inuit to see this is an exhibition that is for them.”

‘An exciting future for Inuit art’

The exhibition features work spanning nearly a century and includes 13 new commissions, roughly 20 major national and international loans, and works drawn from the WAG and the Government of Nunavut’s collections.

Each of the curators brought in works by artists they’re related to, “so we thought of this as our ancestors’ installation,” Igloliorte notes. An intricate carving by Ulujuk Zawadski’s great-grandfather may be the oldest work in the exhibition.

“The exhibition represents a wide range of media that challenges preconceptions of Inuit art, from digital media and installation work, sound art, sculpture, painting, drone photography and much more,” Igloliorte says. “Together these artworks celebrate our past, survey the present and speak to an exciting future for Inuit art.”

Qaumajuq — a name gifted to the museum by Indigenous language keepers, means “it is bright, it is lit” in Inuktitut. With more than 14,000 pieces and another 7,400 on long-term loan, the 17,200 square-metre cultural campus houses the largest public collection of contemporary Inuit art in the world.

Entering the space, visitors see a four-storey glass vault, stretching from the basement to the ceiling, with a collection of paintings, carvings, dolls, sculptures and more.

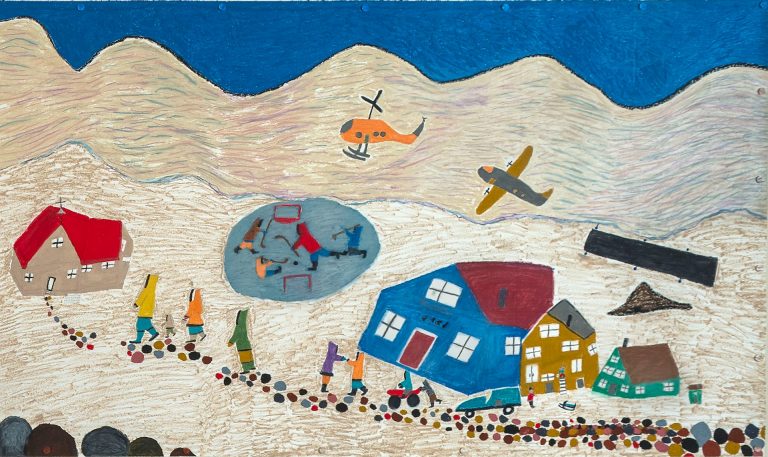

Women At the Fish Lakes, 1977, by Pudlo Pudlat. Inuit (Kinngait), 1916–1992. | Government of Nunavut Fine Art Collection. On long-term loan to the Winnipeg Art Gallery

Women At the Fish Lakes, 1977, by Pudlo Pudlat. Inuit (Kinngait), 1916–1992. | Government of Nunavut Fine Art Collection. On long-term loan to the Winnipeg Art Gallery

‘A chance to share how we see who we are’

Igloliorte says it was key to have Inuit curators lead the INUA exhibition.

“In the last 70 or 80 years of Inuit art history, the opportunity to curate exhibitions, to be leaders in institutions like this and to get to share our perspectives on art have been few and far between,” she says.

“This opportunity provides a chance for us to share how we see who we are. What we want is for Inuit to see an exhibition that is for them and that they recognize parts of their own communities and their lives and their relationships in the artworks.”

Igloliorte was awarded a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) grant in 2018, under which she’s developing Inuit Futures in Arts Leadership: The Pilimmaksarniq/Pijariuqsarniq Project to radically increase Inuit participation in research and arts-based professional practice.

The project provides training and mentorship opportunities to Inuit and Inuvialuit postsecondary students, called Ilinnaqtuit (learners), at associated arts institutions and universities across Canada. The Winnipeg Art Centre is a major partner.

All of the Ilinnaqtuit working on Inuit Futures across Canada have been collaborating with the INUA curatorial team to create Nagvaaqtavut: What We Found, the audio guide for the exhibition. Its contributions include poetic, academic and personal responses provided by the students.

Concordia studio arts undergraduate Jason Sikoak, for example, reflected on visiting with elders in his home community of Rigolet, in his response to a silver teapot in the WAG collection made by artist Michael Massie.

In her contributions, art history PhD student Nakasuk Alariaq responds to several prints made by famous artists from her home community of Kinngait (Cape Dorset, Nunavut).

Christine Qillasiq Lussier, who is completing her MA in Concordia’s Individualized program, reflects on two works from the collection, including an embroidered vest that features an Inuit oral history.

“Working on INUA was incredibly exciting for me as I have had the pleasure to meet, virtually, with fellow Inuit from near and far, and to remain involved within the Inuit community. Above all, I appreciate the work of the Ilinniaqtuit audio guide project because it promotes Inuit representation,” says Lussier.

“It is refreshing and important to experience agency, rather than to be subjects to be researched and discussed about. Being involved in this project has allowed me to reflect about my own experience as an Inuk, and to expand my network by connecting with fellow Inuit in postsecondary education.”

“What’s really exciting about Qaumajuq is that we are going to get the opportunity for more Inuit to get to work there in the future, too; in curatorial processes, in management, in education and across all these different areas where Inuit are going to have the opportunity to lead,” Igloliorte adds.

“By contributing to this audio guide, more emerging Inuit scholars and artists are being introduced to the collections, and to the kinds of research opportunities and careers that are available in the arts.”

According to Stephen Borys, executive director of the WAG, Qaumajuq will play a “critical role” in accommodating cultural workers under Igloliorte’s grant.

The exhibition’s title has two meanings: INUA means spirit or life force in many Arctic dialects, but it also functions as an acronym for Inuit Nunangat Ungammuaktut Atautikkut, or Inuit moving forward together, which Igloliorte says reflects “our collective vision for Qaumajuq.”

INUA, co-curated by Concordia associate professor of art history Heather Igloliorte began March 25 as part of the virtual opening of Qaumajuq in Winnipeg.