Aftermath

The university administration had called the police to remove the protesters. A “specially trained riot squad" dispatched by SPVM meant that students were not arrested by the regular police force.

The university administration had called the SPVM police to remove the protesters. “The staircases and escalators were barricaded with furniture, to protect [the protesters] from siege, while the police encircled the building.” SVPM deployed a “specially trained riot squad … to arrest students who were not arrested by the regular force.”

Intense atmosphere

Detailed first-hand accounts of the arrival and entrance of the police into the Hall Building and the computer centre are published in LeRoi Butcher’s essay The Anderson Affair and in interviews with participants of the protest. The accounts make clear that the arrival of the police and the arrest of the student protesters was a tense and fear-inducing event. In addition to the blockades built by the students, the police barricaded the rear entrance/exit to the computer centre. Protesters were prevented from exiting before and while the police entered. A fire broke out in the computer centre, putting lives at additional risk and causing additional panic. Accounts describe the brutality of the arrests, citing varying degrees of physical assault on protestors. 97 students were arrested and the computer centre sustained extensive damage. One protestor, Coralee Hutchison, was taken to the hospital after suffering head trauma during the confrontation, and later passed away.

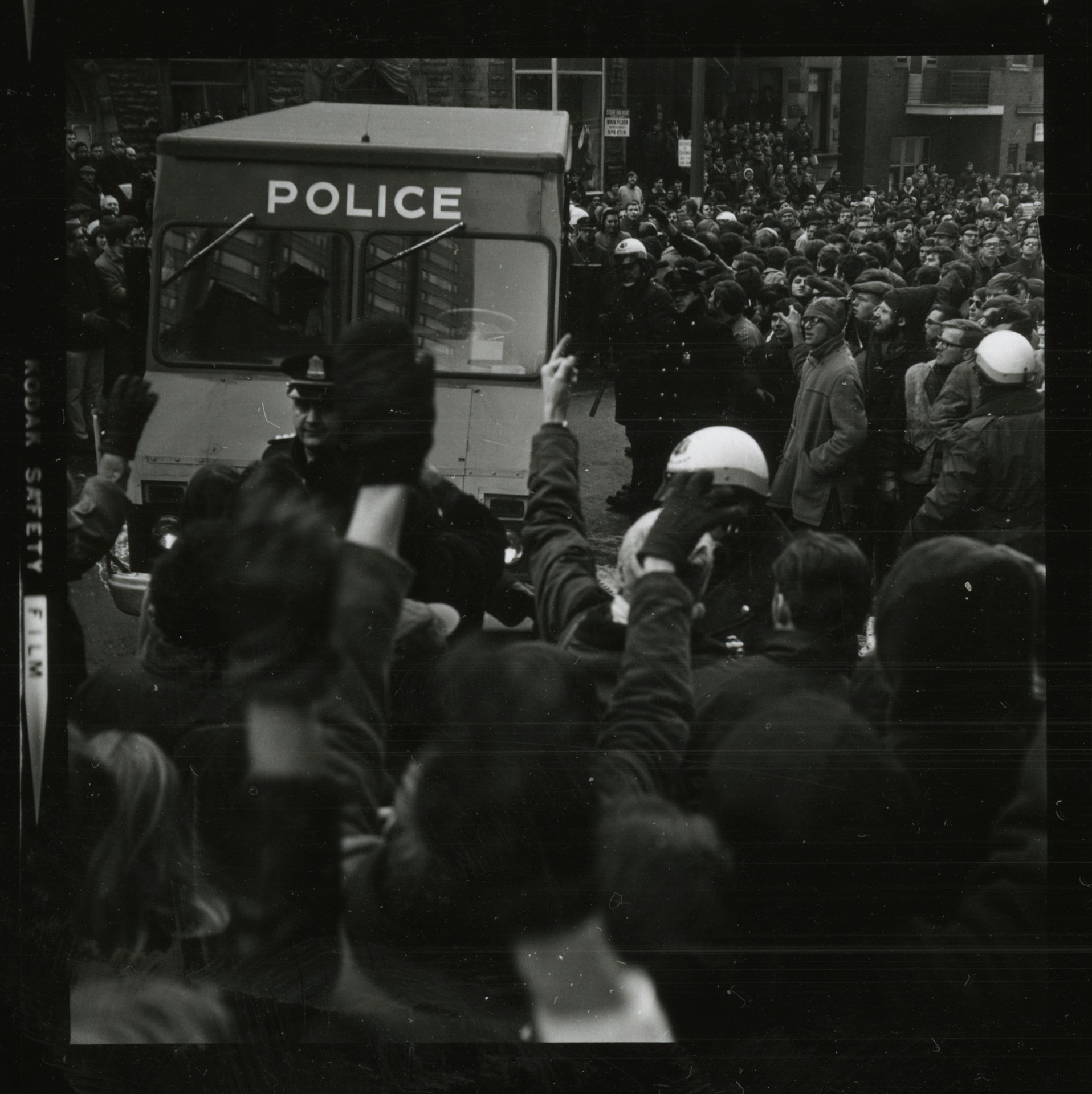

Montreal Police and crowds gathered outside of the Henry F. Hall Building. Source: Concordia University Records Management and Archives

Montreal Police and crowds gathered outside of the Henry F. Hall Building. Source: Concordia University Records Management and Archives

Psychological aftermath

Accounts of the fire that started in the midst of the confrontation between protestors and police convey a deep sense of existential conflict.

“That shook me to my core, of course, because that meant that there are people around who don’t mind seeing other people perish. That hit me hard and I had to come to terms with understanding that human being are capable of doing all manner of things that I never dreamed were possible”

— Anne Cools speaking (Shum, 2015, 0:49:00)

Smoke from the fire, as it burned through the computer centre, attracted a crowd outside the Hall Building. Some White Montrealers watching the arrests shouted violent anti-black slurs from the streets.

“All of that accompanied by the chants of a white mob chanting ‘Let the N*** burn’.”

— Rodney Johnz speaking

“There’s chanting ‘let the N**** burn’, you know , they wanted us to die.. That.. that, you don’t forget”

— Lynne Murray speaking, (Shum, 2015, 0:50:00)

The decisions and outcomes of February 11, 1969, are well detailed from different sides of the confrontation. But close reads of the accounts also reveal a level of confusion, of fear, of rage, and of action experienced in the final hours of the Hall building occupation: the moments when protesters tried to leave the building and were not allowed; when police entered the computer centre but didn’t act immediately; when the police locked the back doors; when an unknown person set a fire; when the riot squad re-entered and used brute force; the racist chants of onlookers on the street. Protesters’ accounts speak to the fear and shock and devastation of understanding how their lives (and Black lives) were valued in those moments.

Social aftermath

Many communities across Montreal profoundly felt the aftermath of the Sir George Williams Affair and the related arrests.

Nancy Warner grew up in Montreal’s Black community and was a student at McGill during the Sir George Williams Affair. She describes the period of Montreal history as a pivotal, defining moment:

“There was the before February 11, there was the day of February 11 and then there was after February 11.

"People from my generation and my parents’ generation, we saw a face of Montreal that we had never seen before. The sheer hostility, the racism, the things that were said to people at work or to people who had nothing to do with Sir George.

"My mother went to work and people said things to her. What we thought were the rules of the game, rules of due process, of people being treated like they had some kind of civil liberties, they were dashed."

Read Nancy Warner’s reflection in “Fifty Years Ago: Reflections on the Sir George Williams University Protests” in Cummings and Mohabir (2019) The Fire That Time: Transnational Black Radicalism and the Sir George Williams Occupation. (4)

Montreal historian Dr. Dorothy Williams highlights a pathway to community relationship-building between the long-established Black Montreal community and Black university students, largely international students from the Caribbean, that emerged following the events of February 11, 1969. The Sir George Williams Affair sparked new efforts to form or reform Black community associations and community groups to address systemic issues impacting Black communities. Williams analyzes the “resurgence of Black print culture” and the Black press in Montreal following the Sir George Williams Affair, which took on the task of countering “mainstream versions” of the narrative reflected in the Montreal press. (5)

Media coverage

Local and national news coverage of the protests and arrests painted the protesters as militant troublemakers, with headlines highlighting violence directed at the university institution, and costs of damages incurred during the occupation. The evening editions of the Montreal Star on February 11, 1969, provides a stark example of the mainstream public narrative. the headline from that issue reads “ Police ordered to move in; Defiant Students Wreck SGWU” and the lede on a front page story from the Montreal Star on February 13, 1969 reads “Canadian immigration forces have teamed up with three police forces to investigate the ‘backgrounds’ of members of the Sir George Williams University ‘occupation forces’”. (6),(7) Extensive damage to the Hall Building from smoke and water was estimated at over $2 million. (8)

The narrative was also divided in the university papers. This special edition of The Paper, one of the regularly published campus newspapers, includes strong sentiments from the administration on the front page, and a chronology of the events on subsequent pages that treats the event with mixed descriptions sometimes referring to protestors as “participants” or “demonstrators” while other times referring to protestors as “black militants.” Strong anti-Black sentiments are expressed throughout the edition. (9)

The arrests left an impact on the community that lasted for years. At the University, internal evaluations ofthe university’s handling of complaints about racism were conducted, and as a result, new rules and rights were adopted in 1971 and the Ombudsman’s Office was created. (8)

Arrest, deportation and backlash

The 97 student arrests were followed by lengthy legal court trials and the deportation of fourteen students to their countries of origin in the Caribbean.

All the students arrested during the event were suspended from university. (10) Some of the students’ suspensions were lifted, while other students faced expulsion. Bail hearings that took place days after the arrests were held in groups. Roosevelt Williams (1971) details the discrepancies in bail set during the hearings, with the lowest bail set for Montrealers (many of whom were white) and the highest bail set for non-Canadian men (who were primarily Black and from the Caribbean). (11) Most students were released on bail except for five students as “Black power ringleaders.” (12) These five students were later released on very high (some of the highest ever set in the municipal court) bonds. Eric Williams, the Prime Minister of Trinidad at the time, posted bail for the Trinidad nationals, following pressure from across the island. Leaders of other Caribbean nations followed suit. (13)

The trials of the students took place in the winter of 1970. Charges ranged from mischief (for juveniles who were tried in juvenile courts) to conspiracy. Consequences of the trials ranged from fines to prison sentences and deportations.

As so many of the university students under arrest were from abroad, there was significant international interest and backlash. Judge Juanita Westmorland-Traoré (an attorney with the defense team in 1969-70) in an interview with Dr. Christiana Abraham, noted the daily presence of embassy staff and that “ambassadors from Trinidad, Jamaica and other Caribbean islands arrived and … gave an impression to the court.” (12) The larger implications of the Sir George Williams Affair impacted political, economic, and transnational/ diplomatic relations between Canada and Caribbean nations; for example, Micheal O West explores the Sir George Williams Affair, the "Trinidad Ten” (the first protestors to be tried in court were a group of students from Trinidad and Tobago), and the Trinidad Revolution in 1970 and other scholars explore the legacy of the affair and the Black Power movement in countries including St Vincient and the Grenadines, Guyana and Jamaica in Cummings and Mohabir, 2021. (2)

Related links

Black consciousness mobilized

Calls for a Black Studies program at Concordia had begun in 1968-1969. Student and community organizations focusing on Black Canadian and diaspora experiences emerged to mobilize for the rights of Black people. These groups advocated for the rights of Black students in the university and for Black studies programs at the university, and also tackled immigration policies, racism in employment practices, etc. (15),(8) Outside Canada, responses to the SGW affair, protests and student arrests included large scale demonstrations against the university’s actions and the Canadian governments. The affair and its outcomes have been described as the “single most important manifestation of Black power in Canada” by David Austin, and as an integral event in the rise of and mobilization of Black power and anti-colonial movements across North America and the Caribbean.(2),(16)

Related link

Biliography

1. Shum, Mina. Ninth Floor. National film Board of Canada, 2015.

2. Cummings, Ronald & Mohabir, Nalini. The Fire That Time: Transnational Black radicalism and the Sir George Williams Occupation. Montreal : Black Rose Books, 2021.

3. Butcher, LeRoi. The Anderson Affair. [book auth.] Dennis Forsythe. Let the Niggers Burn: The Sir George Williams affair and its Caribbean aftermath. Montreal : Black Rose Books, 1971.

4. Bayne, Clarence, Dash, Brenda and Fils-Amié, Philippe, & Warner, Nancy. Fifty Years Ago: Reflections on the Sir George Williams University Protests. [book auth.] Ronald & Mohabir, Nalini Cummings. The Fire that Time: Transnational Black Radicalism and the Sir George Williams Occupation. Montreal : Black Rose Books, 2021.

5. Williams, Dorothy. The Sir George Williams Affair: A watershed in the Black press. [book auth.] Ronald & Mohabir, Nalini Cummings. The Fire That Time: Transnational Black radicalism and the Sir George Williams occupation. Montreal : Black Rose Books, 2021.

6. Steinberg, Victor et Tim BurkePolice orded to move in: Defiant Students Wreck SGWU. The Montreal Star. Evening, 1969, Vol. 101, 35.

7. Conroy, Larry. Immigration will check students. The Montreal Star. Evening, 1969, Vol. 101, 37.

8. Lambert, Maude-Emmanuelle and Ma, Clayton. Sir George Williams Affair. The Canadian Encyclopedia. [Online] December 20, 2016. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sir-george-williams-affair.

9. The Evenings Students Association. The Paper - Special Edition. Special Edition, 1969, February 11.

10. Office, Information. News Release: University Position on Suspensions. rma sgw publications. 1969-03-25.

11. Williams, Roosevelt. Réctions: The myth of white "backlash". [book auth.] Dennis Forsythe. Let the Niggers Burn: The Sir George Williams University affair and its Caribbean aftermath. Montreal : Black Rose Books, 1971.

12. Abraham, Christiana. An interview with Judge Juanita Westmorland-Traoré. [book auth.] Ronald & Mohabir, Nalini Cummings. The Fire that Time: Transnational Black radicalism and the Sir George Williams occupation. Montreal : Black Rose Books, 2021.

13. Lumumba, Carl. The West Indies and the Sir George Williams Affair: An assessment. [book auth.] Dennis Forsythe. Let the Niggers Burn: The Sir George Williams University Affair and its Caribbean aftermath. Montreal : Black Rose Books, 1971.

14. Forsythe, Dennis, ed. Let the niggers burn: The Sir George Williams University affair and its Canadian aftermath. Montreal : Our Generation Press, 1971.

15. President's Task Force on Anti-Black Racism Final Report. Montreal : Concordia University, 2022.

16. Austin, David. All Roads Led to Montreal : Black power, the Caribbean and the Black Radical Tradition in Canada. The Journal of African American History. 92, 2007, Vol. 4, pp. 516-539.

17. —. All Roads Led to Montreal : Black power, the Caribbean and the Black Radical Tradition. The Journal of African American History. 92, 2007, Vol. 4.

Contact us

If you have any questions or comments, please contact blackperspectives@concordia.ca