Historical context

'While Canada was founded on the embrace of British imperial values, some of its leaders and institutions have asserted that Canada was not founded on systems of white supremacy.'

Black presence and immigration context in Montreal and Canada

Black communities in Montreal are part of the city's long, rich, and complicated history.

The presence of Black individuals in colonial New France has its roots in the transatlantic slave trade of the 17th century, where Black and Indigenous people were enslaved for their forced labour in the homes of wealthy families and religious orders. As a colony of France, slavery was authorized and regulated by the French "Code Noir" in 1689 and legalized in 1709. Under this law, free Black individuals were "constantly at risk of being enslaved."(1) While slavery was abolished in the British colonies (including the colonial territory to become Quebec) in 1834, the use of enslaved Black and Indigenous people as slave labour allowed elite merchants, the church and the colonial governments to build wealth, expand the empire, and "develop the economic, social and political foundations of several major Canadian (Quebec and Montreal specific) institutions."(2)

After abolition, freed Blacks remained in Montreal. Black Montrealers worked in the developing railway system in the 19th century as part of the railroad porter labour force. Black Montrealers of Canadian, West Indian, and American lineages primarily lived in the southwestern district of Montreal, St. Antoine. As Montreal-based historian Dr. Dorothy Williams explains, "Black concentration around rail and transportation depots reflected the strong economic relationship between the transportation industries and Black labour."(3)

While there were no legally enforceable segregation laws, discriminatory practices in hiring and renting were common. Though immigrants coming to Montreal from the Caribbean were highly skilled and trained craftspeople, teachers, and nurses, newcomers were often forced to "settle for meagre opportunities," day labour, or in positions where job advancement possibilities were low.(3)

Though Black Montrealers faced underemployment, poor working conditions, low pay, housing discrimination, and other daily forms of racism, Black social organizations helped create stability. They supported the values, dreams, and flourishing of the Black community. The first Black community institutions in Montreal were founded between 1902–1927. They provided spaces and its members played crucial roles in the community, including advocating for better living conditions, providing community aid, supporting political associations, organizing education and enrichment programs for youth and contributing to the community's intellectual life(3).

Canadian immigration policies of the 20th century severely restricted immigration opportunities for citizens of Caribbean nations and British colonies. Black immigrants were recruited intermittently under temporary labourer status, however, settlement and family reunification were difficult under these practices.(4) The Canadian government deployed a host of tactics and overtly racist policies, such as the 1911 Order-in Council 1324 policy which created a ban on Black immigration from 1911 to 1912, citing the unsuitability of Black people to the climate and requirements of Canada.(5) Later policies targeted recruitment to support labour needs by the Quebec government and industry led to an increased presence of Caribbean women, who migrated under severe restrictions, to work in caregiving roles as nurses and domestic workers in the 1950s and 1960s. Though formal policies of racial exclusion were eventually revoked and the narrative of immigration to Canada re-written, the legacy of the policies continued to perpetuate racial and ethnocultural bias and limitations on full participation in society.(4)

These broader contexts, as well as other transnational political and economic relations (such as Canada’s relations with Anglo-Caribbean colonies, and turmoil and political repression experienced under the dictatorship of François Duvalier in Haiti) led to a significant increase in Caribbean students coming to Montreal in the late 1960s to pursue university studies.

Social unrest and civil rights movements

Questioning Canada's foundations

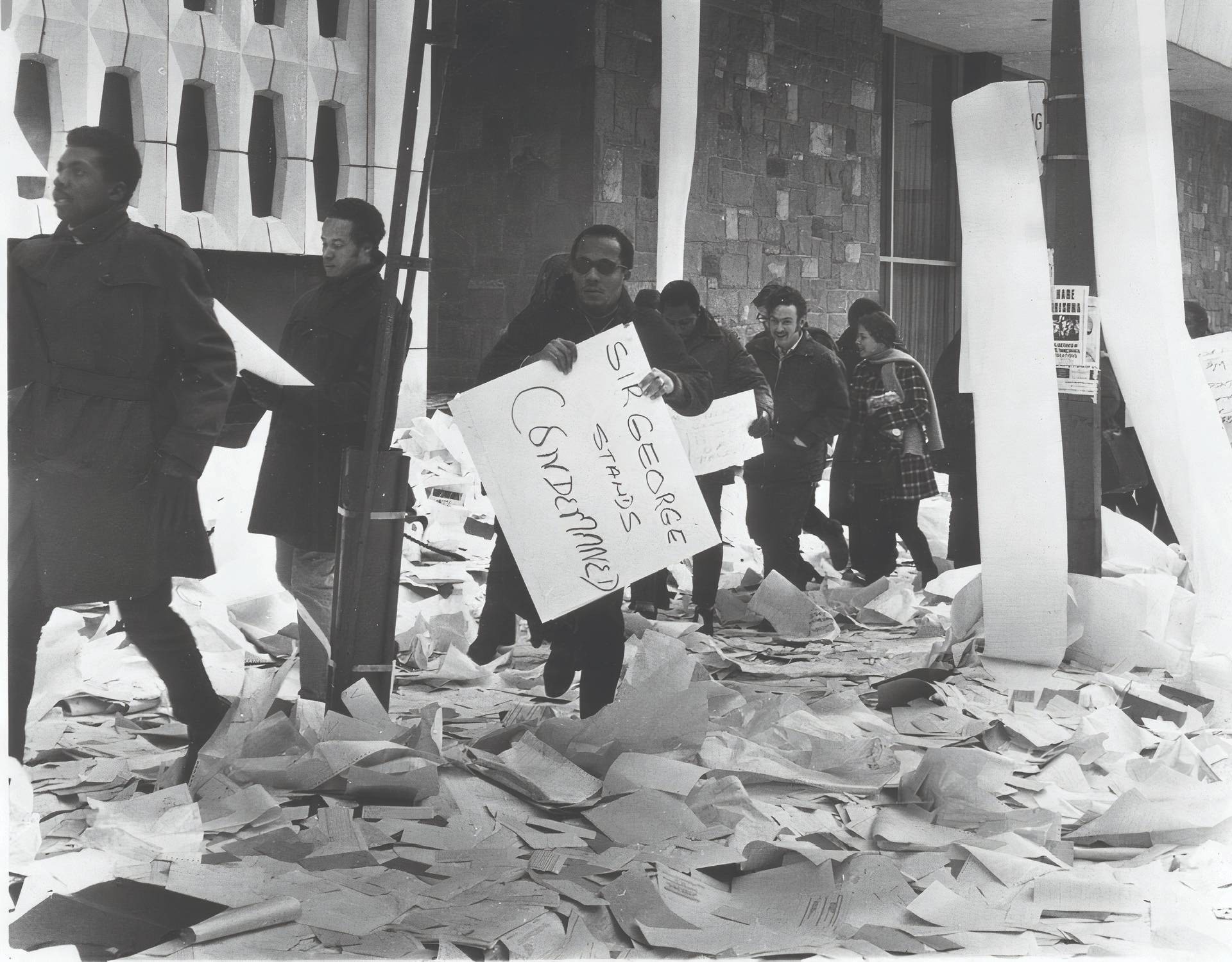

The 1969 Sir George Williams University student protest was a pivotal moment in the struggle against anti-Black racism in Canada. It strongly influenced racial politics in Canada by raising awareness of anti-Black racism that had remained until that time, largely unacknowledged.

The student protest drew inspiration and was largely informed by the civil rights and Black Power movements in the United States, cementing Canada's legacy around the world as a country founded on institutional racism.

Also in 1968, worldwide protests were advocating for the civil rights of peoples who continued to be treated as colonial subjects.

The era of consciousness-raising

"Most observers, along with myself, agree that the various conferences that were held in Montreal were part of the antecedents to the 'Anderson Affair'...on the substantive grounds that before there can be any action at all on the part of a minority group, that group needs to be mobilized mentally and ideologically"

— Dennis Forsythe(6)

The occupation of the computer centre at Sir George Williams University in protest of institutional racism took place from January 29 to February 11 of 1969, but the "Anderson Affair" began as a formal grievance filed to the university in April of 1968. Michael O. West, a historian of global perspectives of the Black Power movement, describes 1968 as a "momentous and majestic year … a year of protest and rebellion worldwide"(7). West contextualized the Sir George Williams events within civil rights struggles and anti-colonial movements taking place across the globe in 1968, including the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., racialized struggles in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), civil war in Nigeria, the Trinidad Revolution, and anti-war activism.

Political action for Black liberation was building substantial momentum in April 1968, including through the memorial march and rally following the assassination of King Jr., organized in part by Sir George Williams students like Rosie Douglas (later involved in the occupation of the computer centre). The event was created to pay tribute to the civil rights leader and draw attention to Black struggle and liberation in Montreal(7; 8) The six Black students in Perry Anderson's biology class filed their grievance to the university shortly after this rally.(7)

Beginning in 1965, the Black community of Sir George Williams University organized an annual conference about the involvement of the Black community in Canadian society. In October 1968, the event adapted a "pragmatic" orientation to discuss and mobilize for access and participation in the "decisions affecting [Black] lives. One week later at McGill, the Congress of Black Writers, an international gathering of Black intellectuals and radicals including Stokely Carmichael, Walter Rodney, and C.L.R. James, took place, focusing on the history and struggles of people of African descent worldwide.(6; 9)

LeRoi Butcher shares insight into how Black consciousness-raising and transformation evolved at Sir George Williams:

"In other words, Anderson [The Anderson Affair] just happened to fit into a historical sequence, the dialectics of which had begun outside of the university realm. There was the history of slavery and colonization of Blacks; there was the day-to-day injustice in housing, employment, immigration, etc; there was the new wave of consciousness sweeping the United States, which caught on at the Congress of Black Writers. There was the incident in Halifax where Rosie Douglas from Montreal, on a trumped-up arrest for loitering, boldly declared himself an African living in the Western World by force and not by choice. Blacks in Montreal rallied morally and financially to his support; there was the case of the Caribbean Society at Sir George being refused an office when other groups with fewer members were given office space. Black students were mobilized to demand an office successfully … Against this background of the development into a conscious and cohesive unit … the complaints against Anderson ceased to be an individual thing and soon became a Black student issue."(10)

Political struggles in universities

As the late 1960s was a historic period of civil rights and anti-colonial struggles, colleges and universities were incubators of civic action reflecting the concerns of society at large, including racism, war, and democratic participation and power.(11; 12)

In a study of student protests at colleges and universities, the Urban Research Corporation of Chicago reported 292 major protests on 232 college and university campuses in the United States during the first six months of 1969.(6;13) Half the documented protests concerned Black recognition and the needs and demands of Black students, including demands for Black Studies programs, increases in Black faculty, and recourses for discrimination issues.(13)

Dennis Forsythe uses this report to put the Sir George Williams Affair into a larger context of university protests across North America, where Black students and allies were revealing and resisting universities' racist political, social, and economic dynamics. "Forsythe also names the Sir George Williams Affair as more than a student revolt, but a "Black student protest" as the events "escalated from a classroom conflict to an international race-conflict"(6). To that end, David Austin describes the Sir George Williams Affair as "the single most important manifestation of Black Power in Canada."(14)

Sir George Williams protest. ©The Gazette

Sir George Williams protest. ©The Gazette

Bibliography

1. McRae, Matthew and Steve McCullough. The story of Black slavery in Canadian history. Canadian Museum for Human Rights. [Online] February 16, 2023. [Cited: May 18, 2023.]

2. hampton, rosalind. Racialized social relations in higher education: Black student and faculty experiences of a canadian university. Montreal: McGill University, 2016.

3. Williams, Dorothy. The Jackie Robinson myth: social mobility and race in Montreal 1920-1960. Montreal: PhD Dissertation, Concordia University, 1999. p. 33.

4. Raska, Jan. Recruiting Domestic Workers and Live-In Caregivers in Canada. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. [Online]

5. Order-in-Council PC 1911-1324. Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. [Online] [Cited: May 17, 2023.]

6. Forsythe, Dennis, ed. Let the niggers burn: The Sir George Williams University affair and its Canadian aftermath. Montreal : Our Generation Press, 1971.

7. West, Michael O. On Fire: The Crises at Sir George Williams University (Montreal) and the Worldwide Revolution of 1968. [book auth.] R. & Mohabir, N. Cummings. The fire that time: transnational black radicalism and the Sir George Williams occupation. Montreal : Blck Rose Books, 2021.

8. Hébert, P.C. "A Microcosm of the General Struggle": Black thought and activism in Montreal 1960-1969 (Doctoral Dissertation). s.l. : University of Michigan, 2015.

9. President's Task Force on Anti-Black Racism Final Report. Montreal : Concordia University, 2022.

10. Butcher, LeRoi. The Anderson Affair. [book auth.] Dennis Forsythe. Let the Niggers Burn: The Sir George Williams University Affair and its Caribbean Aftermath. Montreal : Black Rose Books, 1971, pp. 76-109.

11. Sheppard, Peggy. The relationship between student activism and change in the university: With particular reference to McGill University in the 1960s. Montreal: escholarship.mcgill.ca, 1989.

12. Cummings, R. & Mohabir, N. The Fire That Time: Transnational black radicalism and the Sir George Williams Occupation. Montreal : Black Rose Books, 2021.

13. Herbers, John. Analysis of Student Protests Finds Most Nonviolent, With New Left a Minor Factor. New York Times. Online, January 14, 1970.

14. Austin, David. All Roads Led to Montreal : Black power, the Caribbean and the Black Radical Tradition in Canada. The Journal of African American History. 92, 2007, Vol. 4, pp. 516-539.

Contact us

If you have any questions or comments, please contact blackperspectives@concordia.ca