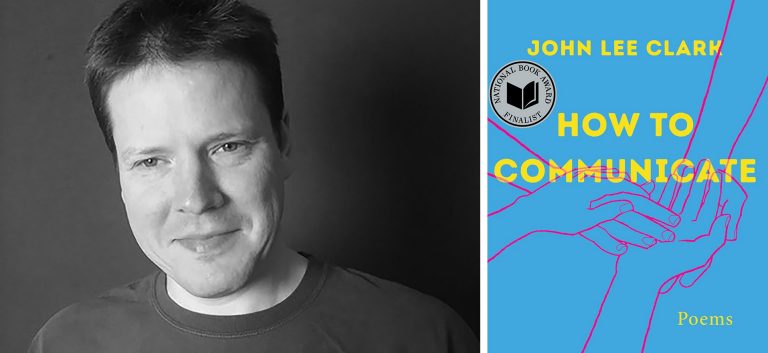

John Lee Clark receives the $100K Miriam Aaron Roland Graduate Fellowship

John Lee Clark, a PhD student in Concordia’s Humanities Interdisciplinary program, is the recipient of the 2024 Miriam Aaron Roland Graduate Fellowship. A renowned DeafBlind poet and researcher, Clark researches Protactile — a new language emerging within the DeafBlind community. His unconventional academic path reflects his deep commitment to exploring how knowledge and experience can be shared without sight.

“John Lee Clark’s approach to learning and research is profoundly reshaping how we think about education, knowledge and language,” explains Pascale Sicotte, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Science.

“With the support of the Miriam Aaron Roland Graduate Fellowship, his innovative work in Protactile language promises to push the boundaries of communication and bring new perspectives to academia.”

Each year, two doctoral students receive the fellowship, valued at $100,000 and distributed across the four years of a PhD program. The fellowship recognizes Concordia students whose interdisciplinary research enhances the university’s research profile.

Below, Clark shares his thoughts on his academic journey, research and the transformative impact of Protactile.

‘Each tactile detail is an experience worth savouring, just like every step in my research journey’

Where are you from? Can you tell us a bit about your academic journey?

John Lee Clark: I was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, and lived there before moving to Montreal. My academic journey, however, is a bit unconventional. My true education comes from my community, which has historically been outside of traditional academic spaces. School has always been somewhat tangential to my learning process. Interestingly, the higher I go in my studies, the easier it is to align academic pursuits with the way I naturally learn.

In terms of credentials, I hold a BA in DeafBlind studies and an MFA in creative writing. I’ve worked on research projects funded by the National Science Foundation, the United States Department of Education and the National Endowment for the Arts, all of which focus on Protactile — our language and the many ways it’s reshaping communication and arts.

What made you choose Concordia?

JLC: I wasn’t actively looking to pursue a PhD, but my decision changed when I encountered the work of Erin Manning, a professor here at Concordia. She’s asking the same questions I’ve had, though I hadn’t been able to fully articulate them until now. Manning's work that relates to touch, tactile communication and relationality, along with the interdisciplinary opportunities at Concordia, made it clear that this is where I needed to be.

What is your research about?

JLC: In a word — everything. The more precise question is how I research. Protactile is a language unlike any other. It’s tactile, relying on dynamic interactions and two types of touch-based perception. We’re living in a revolutionary moment for our community.

Traditionally, we’ve been forced to approach subjects through the lens of sight. For instance, if a DeafBlind person wanted to study botany, they’d need a sighted person to describe what was under the microscope. Protactile changes that. It asks how we can conduct research in fields like botany without relying on sight and instead develop methods that come from within our tactile experiences.

It’s not just about learning what’s out there — it’s about fundamentally questioning how knowledge is generated, experienced and shared. Protactile opens up new pathways for discovery across a wide range of subjects.

What does it mean to you to receive this fellowship?

JLC: It’s incredibly meaningful. It feels like a warm welcome from Concordia. On a practical level, it allows me to fully focus on my research, which is intricately linked to every aspect of my life. I can’t separate life from study — it’s all one continuous exploration.

What are your plans for the next few years?

JLC: My process is more about discovery than pursuing a specific endpoint. Right now, I’m directing a DeafBlind living history project — the first of its kind — where we’re exploring how tactile experiences can evoke history. For example, we’re finding that polyester, despite its appearance, doesn’t feel historically accurate.

Next term, I’ll be delving deeper into tactile aesthetics, especially in how objects are contextualized. Pedestals, for instance, isolate and sterilize objects. I’m interested in re-ecologizing them by creating tactile environments.

Many books will come out of these processes, and one of them will eventually become my dissertation, though I’m not yet sure which one.

Is there anything you would like to tell Miriam Aaron Roland?

JLC: Rather than telling her something, I’d take her on a Protactile tour. I’d show her all the small, often-overlooked things that are rich with tactile detail — like a particular floorboard creaking or the craftsmanship of a door hinge that you’d never find at Home Depot.

I’d show her a specific branch of a cherry tree — not just any branch, but this one — and invite her to feel the grooves, which are neither too thick nor too thin. Each tactile detail is an experience worth savouring, just like every step in my research journey.

Find out more about Concordia’s School of Graduate Studies.