Concordia oral history exhibition opens in Rwanda

Concordia’s Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling (COHDS) hosted the first version of the exhibit Mapping Memory – Atlas of Rwandan Life Stories in spring 2023.

On display were the results of years of research conducted in collaboration with PAGE RWANDA, the Association of Parents and Friends of Victims of the Rwandan Genocide.

Members of Montreal’s Rwandan community shared life stories that were subsequently mapped into the digital Atlas of Rwandan Life Stories. The results of an intimate cartographic collaboration were also on display.

The exhibition is now on display at the Kigali Genocide Memorial until June 16 as part of the 30th commemoration of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi of Rwanda.

Exhibition launch attendees at the Kigali Genocide Memorial earlier this week.

Exhibition launch attendees at the Kigali Genocide Memorial earlier this week.

Compiling Memories

The current project grew out of the Montreal Life Stories project headed by Steven High, Concordia professor of history and co-founder of COHDS.

Over a five-year period, university and community-based researchers recorded the accounts of nearly 500 Montreal residents who had been displaced by war, genocide and other human rights violations. Roughly 80 of these interviews came from Montreal’s Rwandan community.

Sébastien Caquard, former co-director of COHDS and professor in Concordia’s Department of Geography, Planning and Environment, began mapping these stories in an effort to better understand the complex relationships that exist between places, narratives and memories.

Caquard consulted the community for feedback throughout this process, and a relationship developed between COHDS and PAGE RWANDA.

“Most people share their stories because they want others to hear them,” says Caquard. “Mapping became a way to share those stories.”

As founder and director of the Geomedia Lab, Caquard led the development of Atlascine. Designed for this specific project, the open source mapping application has been used to produce several online atlases, including Raconte-moi Riopelle.

To date, 22 stories have been compiled into the Atlas of Rwandan Life Stories.

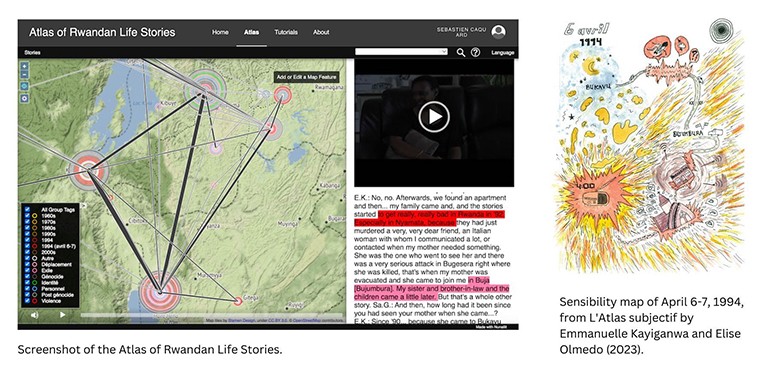

At left: Screenshot of the Atlas of Rwandan Life Stories. | At right: Sensibility Map of April 6-7, 1994, from l’Atlas subjectif by Emmanuelle Kayiganwa and Elise Olmedo (2023).

At left: Screenshot of the Atlas of Rwandan Life Stories. | At right: Sensibility Map of April 6-7, 1994, from l’Atlas subjectif by Emmanuelle Kayiganwa and Elise Olmedo (2023).

The whole story

As Caquard explains, mapping entails a great deal of editing and interpretation that is not appropriate in the handling of traumatic memories. “We were very uncomfortable telling people, ‘this is the map of this story,’” he shares. So they expanded the map to include each story in full.

“You can see what’s been mapped and you can see how,” says Caquard. “Visitors can navigate through the story or the map — however they want. We mapped it that way for a reason, but you can always challenge that.”

Members of the Rwandan community tell Caquard that transmission of these stories, in this way, is doubly valuable. Not only does the format educate Rwandan youth in an interactive and mediated way — enabling access to difficult stories and prompting conversations — it also counters denialism.

As Caquard notes, there are many who would like to suggest that this genocide was not ethnically motivated. “We want to make sure people know it was not a civil war,” he says. “We need to preserve these stories; they are part of transmitting this to the public.”

Mapping emotion

Concordia Banting Postdoctoral Fellow Élise Olmedo began studying specific moments in further depth. Her collaboration with two participants resulted in the creation of hand-drawn sensibility maps.

Inspired by her involvement in this process, Emmanuelle Kayiganwa began assembling photographs and text, collaborating with Olmedo to tell the story of her childhood. For Kayiganwa, collaborative mapping is an opportunity to share the emotions she carries with her.

In consultation with the Rwandan community, it was decided that there should be an exhibition at COHDS to share how the atlas and sensibility maps work.

As Caquard recounts, the already tight-knit Rwandan community came out in droves to spend time at the exhibition. This prompted participant Marie-Josée Gicali to propose that the exhibit also be shown in Kigali.

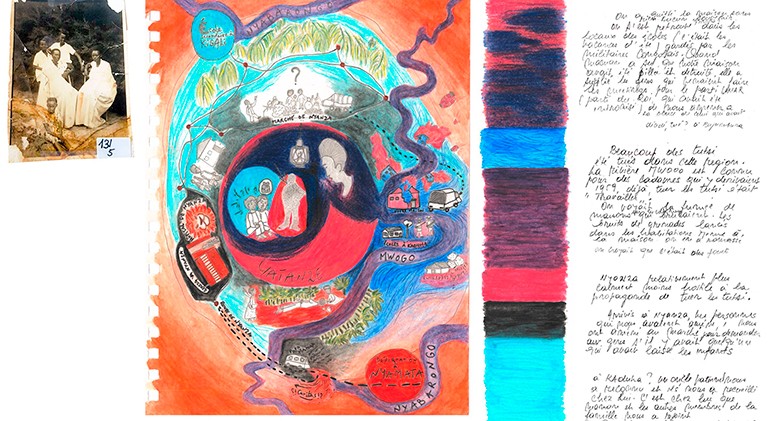

Detail of “La carte de l’enfance.” This poster was co-created by Élise Olmedo and Emmanuelle Kayiganwa.

Detail of “La carte de l’enfance.” This poster was co-created by Élise Olmedo and Emmanuelle Kayiganwa.

A cartographic memorial

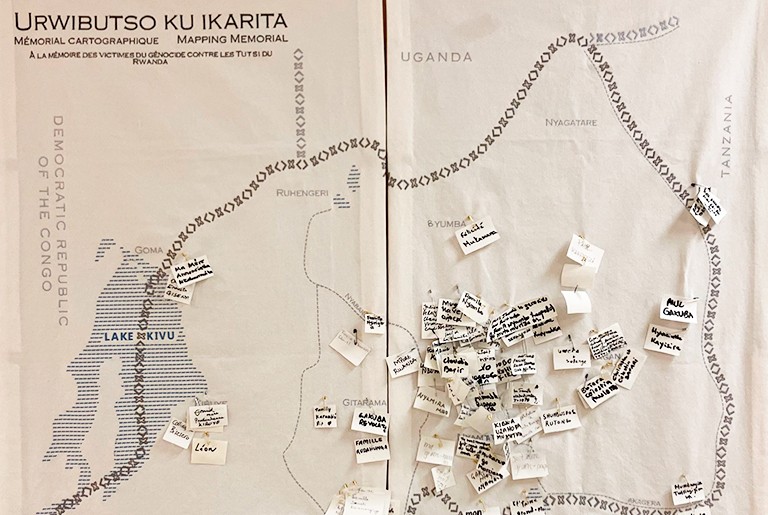

In April 2024, Montreal’s Rwandan community commemorated the 30th anniversary of the genocide, gathering at Cathédrale Marie-Reine-du-Monde. A textile map was displayed and survivors were invited to mark the names of victims and significant places.

These names are being transferred to a larger cartographic memorial that will receive further contributions at the Kigali Genocide Memorial.

Caquard, Gicali and Kayiganwa will all be in attendance, as will Kassy Irebe — one of several Concordia students working on the project. Originally from Rwanda, Irebe will assist in filming and documenting the exhibit.

Transmitting — and providing space for engagement with — shared traumatic memory of the 1994 Rwandan genocide has always been central to this project.

View of the cartographic memorial with contributions from members of the Montreal Rwandan Community.

View of the cartographic memorial with contributions from members of the Montreal Rwandan Community.

“Telling a story is an opportunity, a gift from heaven, that was offered to me with grace,” Kayiganwa says. “There are real parts of the story which are very painful and unreal for those who have not experienced it.

“Working together on this story, however, has created a serenity to continue. Thanks to you and thanks to all those who are committed to provide a space to the denied humanity that led to the genocide of the Tutsi.”

![]()

Explore the digital Atlas of Rwandan Life Stories.

Mapping Memory – Atlases of Rwandan Life Stories will be exhibited at the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Rwanda from June 7 to 16.